Barbara Kingsolver's The Poisonwood Bible ... I'm not sure exactly where to start. It was published in 1998, and centers around a family from Georgia, U.S.A. who move to the Congo in 1959 with the goal of converting the Congoese people to Christianity. The star characters include Nathan Price, the patriarch of the family and a Baptist minister with a condescending attitude; Orleanna, matriarch of the family who is not so religious as her husband and feels overwhelmed; Rachel, the oldest daughter and a materialistic-minded teenager; Leah, one of the twins and the child who most wants to gain her father's approval and love; Adah, the other twin and a crippled, yet incredibly intelligent, girl who refuses to talk; and Ruth May, the youngest and, as such, the most innocent and openly curious. The book chronicles their life in the Congo and after, including a good amount of history.

Barbara Kingsolver's The Poisonwood Bible ... I'm not sure exactly where to start. It was published in 1998, and centers around a family from Georgia, U.S.A. who move to the Congo in 1959 with the goal of converting the Congoese people to Christianity. The star characters include Nathan Price, the patriarch of the family and a Baptist minister with a condescending attitude; Orleanna, matriarch of the family who is not so religious as her husband and feels overwhelmed; Rachel, the oldest daughter and a materialistic-minded teenager; Leah, one of the twins and the child who most wants to gain her father's approval and love; Adah, the other twin and a crippled, yet incredibly intelligent, girl who refuses to talk; and Ruth May, the youngest and, as such, the most innocent and openly curious. The book chronicles their life in the Congo and after, including a good amount of history.The thing that sets this book apart, in my opinion, is the narrative strategy Kingsolver used. I'm doing this part of the blog post with the help of a peer-reviewed essay by Anne Marie Austenfield, by the way, called, "The Revelatory Narrative Circle in Barbara Kingsolver's The Poisonwood Bible." The book is told from the points of view of each female in the family. The sections are started by Orleanna, who focuses on the motivations and reasons behind both the events of the larger history going on and their own story. After Orleanna's introduction, the girls take over, each taking up the story wherever the last one left off. This leaves the reader with multiple perspectives on a single story. It's a great idea--though it must have been an immense project to write--because it takes the bias of narrators into account. No one character can tell an entire story, so Kingsolver is doing what must be the next best thing (minus third-person omniscient, which is not in vogue right now). So you can get an idea of how this works, here is a list of what the girls each focus on in their chapters:

Leah - historical/cultural details, relationships and emotional connections, integration of prior knowledge

Adah - wonders of nature, absurdity of the human-made world, language, biology, politics, qualities of truth vs. falsity when it comes to human thought and behavior

|

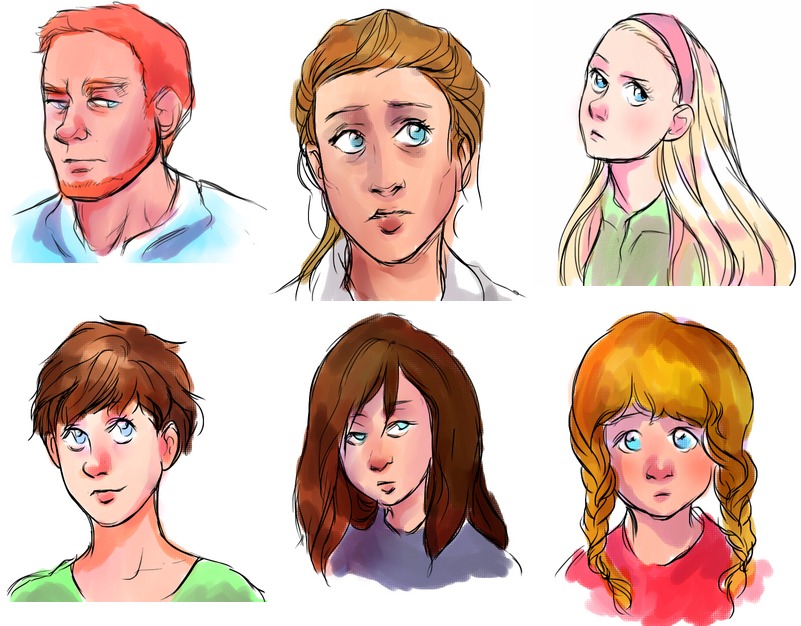

| Picture I found of the Price family - From top left: Nathan, Orleanna, Rachel, From bottom left: Leah, Adah, Ruth May |

The interesting side effect of this style of narration is that this novel has no main character. Each of the narrators are, by turns, both the main character and secondary characters.

When I finished this book, I reread Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, partially because I own it and so it was a simple thing to do and partially because both books are concerned with the white presence in Africa, so I wanted to compare. Biggest difference? Conrad only has one black character who talks; that black person is basically a white person's lapdog, and he only gets one line: "Mistah Kurtz--he dead." This line coming from a white black man makes sense, since it's both Africa saying farewell and the Europeans. Also, Kurtz himself was a black white man. In Poisonwood, black people are talking all the time, starting from page 25 (when they get to the Congoese village) and running through the end of the book. Kingsolver's Africans are real people; Conrad's Africans are a personification of Africa. Looking at them side by side, I feel like Darkness is not about Africa at all. There simply isn't enough Africa in it for it to be about Africa. It is about colonialism, and the story could have taken place anywhere. Poisonwood is undoubtedly about Africa, its people, and the effect of Africa on others. If it were placed anywhere else, the story would necessarily change.

All that said, this book fell short about halfway through. Doing a little more research revealed why: Kingsolver did not write this book to tell a story; she wrote this book to make a point, and that was her entire purpose. It feels like, and is, a message with a story, instead of a story with a message. Like having so much marinara sauce it's tomato soup instead of a nice plate of spaghetti, the message makes this fall flat as a fiction book. According to Austenfield, Kingsolver wrote this as a fictional story because she wasn't able to actually travel to the Congo at the time (she's spent time living there previously, however), so she could not just record the memoirs of those who live there and produce a nonfiction text. Fiction was the next best thing.

I like this book enough that I find myself trying to think of someone I can loan the book to, though I haven't thought of anyone yet. If you're reading this book, and just want a story and not a history lesson, I would suggest reading it up until page 414 and then call it quits. The story is pretty much over at that point, and after page 375, it feels like a giant, 168-page epilogue. It isn't downright bad, it just isn't nearly as good after page 375. I'm saying read until 414 because I think that gives more closure, a sort of resolution.

No comments:

Post a Comment