Friday, January 31, 2014

Today

Today, a rejection email from my college's literary journal. Saddened, but I'll get over it. Rejection happens, people. They don't call this a subjective discipline for nothing.

Saturday, January 25, 2014

15 Books I've Read That Have Stuck With Me

I saw something on Facebook about coming up with a list of the 15 books that have stuck with you/me/whoever. I thought it intriguing, so here's my list. I didn't read all the rules, because I don't care enough about them, but I did see that I was supposed to not spend a ton of time thinking about it. It's possible, then, that this list is flawed. Also, I know it will change over time. Also, it's out of order. I don't want to bother figuring out an order, because it would make me choose favorites.

2. The Giver I don't know that this would be on my list if it weren't for that recent post of mine that mentioned it. So maybe it doesn't belong on this list. Either way, it is a well-done book and is one of the ones I've read in school through the years that I would actually say is in my personal canon.

2. The Giver I don't know that this would be on my list if it weren't for that recent post of mine that mentioned it. So maybe it doesn't belong on this list. Either way, it is a well-done book and is one of the ones I've read in school through the years that I would actually say is in my personal canon.

3. The Book Thief I read this for the first time just this past year, so maybe it won't be on this list in years to come, but I thought it was one of the best books I have ever read. I blogged about this book, too. It is the only war/Holocaust-themed book I have ever read that I did not need to take a break from while reading. It doesn't ignore the Holocaust, but somehow, it feels both real and holy. I'm not sure about holy, but that's the closest word I can think of right now. Death does not seem like the end, and it feels like death is more of a passage into something better. I think it's that perspective that makes this such a good book.

4. Ariana This is a trilogy, I think, but my copy of these books is all in one book, so I'm cheating a little. The first book of the trilogy is the one that has stayed with me, though, if I have to pick. It's by Rachel Ann Nunes and follows a girl's struggle to raise a baby while trying to put her life in order (she was into the drug and party scene before pregnancy, a pregnancy that led to marriage to a terrible husband). It's a beautiful story, and I love it every time I read it. It's one book I can read over and over again; I think all the books on this list are, actually. This book taught me about forgiveness, mourning, and continuing with life even when you have barely any strength to do so.

4. Ariana This is a trilogy, I think, but my copy of these books is all in one book, so I'm cheating a little. The first book of the trilogy is the one that has stayed with me, though, if I have to pick. It's by Rachel Ann Nunes and follows a girl's struggle to raise a baby while trying to put her life in order (she was into the drug and party scene before pregnancy, a pregnancy that led to marriage to a terrible husband). It's a beautiful story, and I love it every time I read it. It's one book I can read over and over again; I think all the books on this list are, actually. This book taught me about forgiveness, mourning, and continuing with life even when you have barely any strength to do so.

5. Pride and Prejudice This was a hard book to add to this list, mostly because it's representing Jane Austen in general. This story is an incredible read. The story and characters (which are the real brilliant part of all of it) are just spot-on. I don't know if it has taught me anything, specifically, but it has stuck with me anyway, as an icon in the world of books.

5. Pride and Prejudice This was a hard book to add to this list, mostly because it's representing Jane Austen in general. This story is an incredible read. The story and characters (which are the real brilliant part of all of it) are just spot-on. I don't know if it has taught me anything, specifically, but it has stuck with me anyway, as an icon in the world of books.

6. Work and the Glory This is a series, so I'm cheating again. It's by Gerald N. Lund, and tells the story of a Mormon pioneer family beginning with Joseph Smith working for their father soon after his marriage to Emma. The characters are well-done and the history helped me learn a lot about the early history of the LDS church. There are little lessons in it, though, that have stuck with me even more than that. Lessons like doing something before gaining a testimony of it, to name just one off the top of my head.

7. Emily This is a book by Jack Weyland, who, admittedly, is not an absolutely brilliant writer. What is great about Jack Weyland's books are the stories. Emily is about a girl (named Emily! No way.) who dreams of being a news anchor, but then she is severely burned in a fire and has to undergo skin graft treatments to her face and upper body . . . maybe her legs, too. I can't remember. This is another LDS book (so was the Ariana thing, but neither Emily nor Ariana are preachy books. Work and the Glory is intense on the church front), but what I love about it and what has stuck with me is the story of a girl becoming a woman.

8. The Secret Journal of Brett Colton Another LDS book. My religion is a big part of who I am, what can I say? I'm not sure if this book will be on this list in years to come, but it is one that I can read and reread with pleasure. It's about a girl whose older brother died while she was still so young she has no memories of him, and now she is trying to navigate high school. Her brother left a journal behind for her, and she reads it and, of course, her life is changed. I guess I like life-changing stories. Never realized that until now.

8. The Secret Journal of Brett Colton Another LDS book. My religion is a big part of who I am, what can I say? I'm not sure if this book will be on this list in years to come, but it is one that I can read and reread with pleasure. It's about a girl whose older brother died while she was still so young she has no memories of him, and now she is trying to navigate high school. Her brother left a journal behind for her, and she reads it and, of course, her life is changed. I guess I like life-changing stories. Never realized that until now.

9. The scriptures I really don't think this needs much explanation.

10. Waiting for Godot This is a play, actually, by Samuel Beckett, and I've only ever read it in French. Setting that aside, it's an absurdist play wherein Beckett pretty much did his best to erase plot altogether. So the second act mirrors the first act, except for a few changes here and there. I once wrote an essay for a class that examined plot, and I used this play as well as something else I can't remember. But whenever I think about plot, I think about Waiting for Godot.

11. Harry Potter This is a series that changed our culture. It's also a set of books that could probably still make me cry, even though I know what happens in them now. I love the ideas about family and support and love for others. This series deserves all the hype it got, hands-down.

12. Circle of Magic This is a quartet of books by Tamora Pierce. I think I've thrown the one-book-only rule out the window. Whoops. I don't know why, but whenever I think about fantasy, this is one of the series or books that comes to mind. It was a favorite, possibly my favorite, set of books while I was younger. I still love Tamora Pierce and would recommend her to any teenager who loves fantasy like that.

12. Circle of Magic This is a quartet of books by Tamora Pierce. I think I've thrown the one-book-only rule out the window. Whoops. I don't know why, but whenever I think about fantasy, this is one of the series or books that comes to mind. It was a favorite, possibly my favorite, set of books while I was younger. I still love Tamora Pierce and would recommend her to any teenager who loves fantasy like that.

13. Elements of Style It feels so weird to include this book in this list, but it's true. I've read Elements of Style by Strunk and White from front to back one and a half times, as far as I recall. I thought it was entertaining, and pieces of it come to mind while I'm writing, telling me how to do so better.

14. Mere Christianity I adore this book, probably because it approaches Christianity from an angle I enjoy, that is, a logical and analytic angle. I learned so much about Christianity by reading this.

14. Mere Christianity I adore this book, probably because it approaches Christianity from an angle I enjoy, that is, a logical and analytic angle. I learned so much about Christianity by reading this.

15. The Picture of Dorian Gray There are concepts from this book that pop up in my life, that I think about a lot. One of those concepts actually factors into a story I'm worldbuilding for right now. This is a book I think I've only read once (though I own it), but it has stayed inside my mind and comes to life now and again.

Other books I considered include: The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, H.G. Wells' The Time Machine, Great Expectations, David Copperfield, Mistborn, and a whole troupe of others.

15 Books I've Read That Have Stuck With Me

1. The Little Prince This is a book I carry in my purse, partially because it's small enough to fit, partially because it is comprised largely of episodes and so is good for reading from randomly, partially because it helps me practice my French, and partially because I love it so much. There are a lot of lessons in there, and I am always seeing something new. 2. The Giver I don't know that this would be on my list if it weren't for that recent post of mine that mentioned it. So maybe it doesn't belong on this list. Either way, it is a well-done book and is one of the ones I've read in school through the years that I would actually say is in my personal canon.

2. The Giver I don't know that this would be on my list if it weren't for that recent post of mine that mentioned it. So maybe it doesn't belong on this list. Either way, it is a well-done book and is one of the ones I've read in school through the years that I would actually say is in my personal canon.3. The Book Thief I read this for the first time just this past year, so maybe it won't be on this list in years to come, but I thought it was one of the best books I have ever read. I blogged about this book, too. It is the only war/Holocaust-themed book I have ever read that I did not need to take a break from while reading. It doesn't ignore the Holocaust, but somehow, it feels both real and holy. I'm not sure about holy, but that's the closest word I can think of right now. Death does not seem like the end, and it feels like death is more of a passage into something better. I think it's that perspective that makes this such a good book.

4. Ariana This is a trilogy, I think, but my copy of these books is all in one book, so I'm cheating a little. The first book of the trilogy is the one that has stayed with me, though, if I have to pick. It's by Rachel Ann Nunes and follows a girl's struggle to raise a baby while trying to put her life in order (she was into the drug and party scene before pregnancy, a pregnancy that led to marriage to a terrible husband). It's a beautiful story, and I love it every time I read it. It's one book I can read over and over again; I think all the books on this list are, actually. This book taught me about forgiveness, mourning, and continuing with life even when you have barely any strength to do so.

4. Ariana This is a trilogy, I think, but my copy of these books is all in one book, so I'm cheating a little. The first book of the trilogy is the one that has stayed with me, though, if I have to pick. It's by Rachel Ann Nunes and follows a girl's struggle to raise a baby while trying to put her life in order (she was into the drug and party scene before pregnancy, a pregnancy that led to marriage to a terrible husband). It's a beautiful story, and I love it every time I read it. It's one book I can read over and over again; I think all the books on this list are, actually. This book taught me about forgiveness, mourning, and continuing with life even when you have barely any strength to do so. 5. Pride and Prejudice This was a hard book to add to this list, mostly because it's representing Jane Austen in general. This story is an incredible read. The story and characters (which are the real brilliant part of all of it) are just spot-on. I don't know if it has taught me anything, specifically, but it has stuck with me anyway, as an icon in the world of books.

5. Pride and Prejudice This was a hard book to add to this list, mostly because it's representing Jane Austen in general. This story is an incredible read. The story and characters (which are the real brilliant part of all of it) are just spot-on. I don't know if it has taught me anything, specifically, but it has stuck with me anyway, as an icon in the world of books.6. Work and the Glory This is a series, so I'm cheating again. It's by Gerald N. Lund, and tells the story of a Mormon pioneer family beginning with Joseph Smith working for their father soon after his marriage to Emma. The characters are well-done and the history helped me learn a lot about the early history of the LDS church. There are little lessons in it, though, that have stuck with me even more than that. Lessons like doing something before gaining a testimony of it, to name just one off the top of my head.

7. Emily This is a book by Jack Weyland, who, admittedly, is not an absolutely brilliant writer. What is great about Jack Weyland's books are the stories. Emily is about a girl (named Emily! No way.) who dreams of being a news anchor, but then she is severely burned in a fire and has to undergo skin graft treatments to her face and upper body . . . maybe her legs, too. I can't remember. This is another LDS book (so was the Ariana thing, but neither Emily nor Ariana are preachy books. Work and the Glory is intense on the church front), but what I love about it and what has stuck with me is the story of a girl becoming a woman.

8. The Secret Journal of Brett Colton Another LDS book. My religion is a big part of who I am, what can I say? I'm not sure if this book will be on this list in years to come, but it is one that I can read and reread with pleasure. It's about a girl whose older brother died while she was still so young she has no memories of him, and now she is trying to navigate high school. Her brother left a journal behind for her, and she reads it and, of course, her life is changed. I guess I like life-changing stories. Never realized that until now.

8. The Secret Journal of Brett Colton Another LDS book. My religion is a big part of who I am, what can I say? I'm not sure if this book will be on this list in years to come, but it is one that I can read and reread with pleasure. It's about a girl whose older brother died while she was still so young she has no memories of him, and now she is trying to navigate high school. Her brother left a journal behind for her, and she reads it and, of course, her life is changed. I guess I like life-changing stories. Never realized that until now.9. The scriptures I really don't think this needs much explanation.

10. Waiting for Godot This is a play, actually, by Samuel Beckett, and I've only ever read it in French. Setting that aside, it's an absurdist play wherein Beckett pretty much did his best to erase plot altogether. So the second act mirrors the first act, except for a few changes here and there. I once wrote an essay for a class that examined plot, and I used this play as well as something else I can't remember. But whenever I think about plot, I think about Waiting for Godot.

11. Harry Potter This is a series that changed our culture. It's also a set of books that could probably still make me cry, even though I know what happens in them now. I love the ideas about family and support and love for others. This series deserves all the hype it got, hands-down.

12. Circle of Magic This is a quartet of books by Tamora Pierce. I think I've thrown the one-book-only rule out the window. Whoops. I don't know why, but whenever I think about fantasy, this is one of the series or books that comes to mind. It was a favorite, possibly my favorite, set of books while I was younger. I still love Tamora Pierce and would recommend her to any teenager who loves fantasy like that.

12. Circle of Magic This is a quartet of books by Tamora Pierce. I think I've thrown the one-book-only rule out the window. Whoops. I don't know why, but whenever I think about fantasy, this is one of the series or books that comes to mind. It was a favorite, possibly my favorite, set of books while I was younger. I still love Tamora Pierce and would recommend her to any teenager who loves fantasy like that.13. Elements of Style It feels so weird to include this book in this list, but it's true. I've read Elements of Style by Strunk and White from front to back one and a half times, as far as I recall. I thought it was entertaining, and pieces of it come to mind while I'm writing, telling me how to do so better.

14. Mere Christianity I adore this book, probably because it approaches Christianity from an angle I enjoy, that is, a logical and analytic angle. I learned so much about Christianity by reading this.

14. Mere Christianity I adore this book, probably because it approaches Christianity from an angle I enjoy, that is, a logical and analytic angle. I learned so much about Christianity by reading this.15. The Picture of Dorian Gray There are concepts from this book that pop up in my life, that I think about a lot. One of those concepts actually factors into a story I'm worldbuilding for right now. This is a book I think I've only read once (though I own it), but it has stayed inside my mind and comes to life now and again.

Other books I considered include: The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, H.G. Wells' The Time Machine, Great Expectations, David Copperfield, Mistborn, and a whole troupe of others.

Friday, January 24, 2014

What's Elizabeth Reading? ...Russell (Part 2)

Since this book finally arrived in the mail, I was able to finish it this weekend. So here are my notes on the rest of the short stories in Karen Russell's Vampires in the Lemon Grove. Go here for the first couple stories.

The Seagull Army Descends on Strong Beach, 1979

In this story, I kept waiting for Nal to turn into a seagull, but it didn't happen. The first time I read it, when I was missing parts and only reading the bits I could find online, I thought I must have missed some crucial parts. It felt like something was missing. When I got to read the whole thing, I found out I hadn't missed out on too much. So I still feel like something is missing from this story.

What Makes This Story Work?

Aside from the fact that, for me, it doesn't? Maybe it works because it answers the universal question, "What if?" I feel like that question is the keystone of this story. The seagulls personify possibility that doesn't happen. Since at some point, everyone asks this question, I suppose that is how Russell is trying to connect with her reader.

Now Talk About the Writing, Elizabeth.

This story uses a lot of what one of my English professors calls "insignificant significant detail." The idea is to include details that do not matter to the story, but that help make it more concrete and believable. While it doesn't matter what items the seagulls collect, for instance, Russell includes concrete items in the story -- disconnected retainer wires, for instance. This concrete detail gives an unquestionable reality to what is, providing a subtle foil to all the possibility stuff happening in the plot. Russell always uses concrete detail, but this is more obvious and blatant than usual, so it clearly was no accident.

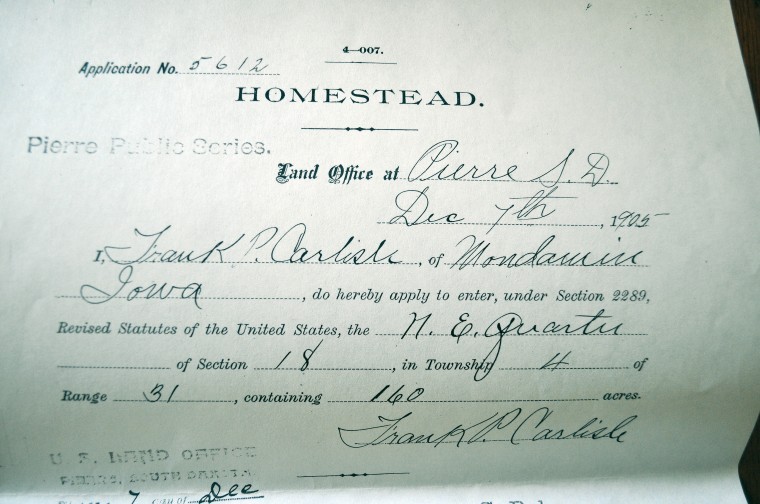

Proving Up

First off (SPOILER ALERT), I think he died midway through the story, in the blizzard. Everything gets surreal after that and he doesn't mention pain or cold. So there you go. (IF YOU AVOIDED THOSE SENTENCES BECAUSE OF THE SPOILER, YOU CAN LOOK BACK NOW) As for this story being about a crisis of faith, as my classmates asserted ... I can see that angle, but I'm not buying it, because I don't think the conclusion contributes fuel to it. I feel like it's a story about the "why" of motivation, which has some tie-ins with hope. The mother has lost hope, the father is blind to the possibility that there's been no purpose to his suffering (maybe a better way to say this is it's a story about purpose?), the dead sisters are a reminder of sacrifice in the name of success and purpose, and that crazed farmer only cares about his purpose and reaching it. The Window, then, symbolizes the success they are striving toward. It is in their grasp, but it just isn't in place yet.

First off (SPOILER ALERT), I think he died midway through the story, in the blizzard. Everything gets surreal after that and he doesn't mention pain or cold. So there you go. (IF YOU AVOIDED THOSE SENTENCES BECAUSE OF THE SPOILER, YOU CAN LOOK BACK NOW) As for this story being about a crisis of faith, as my classmates asserted ... I can see that angle, but I'm not buying it, because I don't think the conclusion contributes fuel to it. I feel like it's a story about the "why" of motivation, which has some tie-ins with hope. The mother has lost hope, the father is blind to the possibility that there's been no purpose to his suffering (maybe a better way to say this is it's a story about purpose?), the dead sisters are a reminder of sacrifice in the name of success and purpose, and that crazed farmer only cares about his purpose and reaching it. The Window, then, symbolizes the success they are striving toward. It is in their grasp, but it just isn't in place yet.What Makes This Story Work?

Creepy + Old West + Clear objective that leads the reader through (we are lead through just like the narrator himself -- again with the reader being in sync with the main character) = It Works. It uses the old and charges it with something new, which is always a good idea (unless the new is stupid). It gives the reader something to stand on, lets them get their bearings, then pulls that foundation out from under their feet, throwing them off-balance and making them admit, "That was cool."

Now Talk About the Writing, Elizabeth.

This story has a better sense of place than her others, but I'm still not feeling it. I did not wonder where my jacket was, for instance, when the blizzard hit. I also did not care about the characters or the plight they were in. Maybe if I'd had experience similar to theirs, it would be different; but how likely is it for someone to have been in any similar situation these days? Not one of Russell's better stories. I don't even feel like talking about the writing it just wasn't splendid.

The Barn At the End of Our Term

The thing I'm learning about Karen Russell is she loves symbolism and puts it into her stories without much camouflage. She is clearly trying to teach something with every short story. In this one, it's about accepting reality with humility and grace. In my opinion, anyway.

Also, as my professor says, "I bet this is funny, but I'm too dumb!" I'm sure there are a lot of jokes in this story any American presidential history buff would find to be hilarious that I don't even recognize as a joke.

Also, as my professor says, "I bet this is funny, but I'm too dumb!" I'm sure there are a lot of jokes in this story any American presidential history buff would find to be hilarious that I don't even recognize as a joke.What Makes This Story Work?

Cultural familiarity with the characters helps a lot. It gives a strange story a solid foundation. We are also on the same page as the characters, which is, as I've said, characteristic of Russell. They don't know why this is going on, we don't know why this is going on. It's another transformation story, which the other stories have prepared the reader for. The sequence helps, though it is not necessary for understanding the stories -- after all, most of these were originally published elsewhere before being included in this collection. The placement of this story is nice because it is a break after the darkness of Proving Up.

Now Talk About the Writing, Elizabeth.

Third-person, free-indirect. She only uses details that further her plot and add some push. I feel like they are in a generic farm, though, which I don't like. Russell does not linger in this story; it makes me think it was probably not her favorite to write.

Dougbert Shackleton's Rules for Antarctic Tailgating

Honestly, I think Russell wrote this because she thought it was a fun idea. Maybe she was teasing sports fans. This could be read more seriously, as the narrative of someone dealing with divorce, but there is scarce evidence for that reading, so I"m going with the hyperbolic-sports-fan reading -- i.e., the obvious interpretation.

What Makes This Story Work?

It's taking something we are all familiar with and placing it in a different environment. Usually, the new is placed in a familiar environment or the familiar in a new, but rarely is that "new" also bizarre. In here, it's bizarre. Somehow, Russell's style makes that a positive thing that really makes this story a stand-out from other sports-themed stories.

Now Talk About the Writing, Elizabeth.

Now Talk About the Writing, Elizabeth.The format for this story is different, given as a list of explanations instead of a linear story. I've experimented with story arcs before, but it has yet to work this well. I think it's because Russell isn't focused on a story, just on explaining a situation. From where I'm standing, that is unique. Also: This is the first story in this collection that speaks directly to the reader. This helps it seem less like a story, too, I think. It is closer to a long blog post than a story. Reading it is not awkward, so that means all this format stuff works.

The New Veterans

What amazed me most about this story was how Beverly was so willing to collect harm to herself in order to help Derek. I think, though, after some reflection just now, that it is a story that highlights how caregivers also suffer from negative side effects via whatever the cared-for person is going through or went through. IN that sense, this is a realistic story. A desire to adopt the pain of others so they won't have to suffer is not unique to this fictional story. I'm glad this side of PTSD is being told. This is, to me, her most powerful story. With these stories, though, it's probably whatever we can relate best to that we see as being most powerful. That is the real beauty of this collection.

What Makes This Story Work?

I feel like this story takes what a lot of people feel and gives it physical representation, but it also gives a warning at the end, in a gentle way, as a suggestion: Is it right to carry others' burdens? What about after they have set them aside and moved on? See above.

Now Talk About the Writing, Elizabeth.

The concrete detail is there again and, as with all these stories, it is clear Russell did her research. The facts aren't included to show off; they are precisely placed to make us believe the narrator is a good masseuse and the vet really is a vet who served in Iraq. The story does not pretend to be anything but fiction (a courtesy to real vets?), but I can suspend enough belief to see the truth (or truth-questing) beneath the fiction. I do hope that makes sense.

The Graveless Doll of Eric Mutis

When this story started, my automatic reaction was something along the lines of, "Oh no." I did not want to read a story about kids being turned into scarecrows then hung in trees in a creepy park. Luckily, that wasn't the story.

What Makes This Story Work?

By this point, the reader is prepared for the darkly bizarre. This story taps into childhood -- from the bully's point of view, which is not common. If you know the city, the place (well done in this piece) gives it an air of the disturbing familiar. If not, the scarecrow will. So Russell has played to audiences from both rural and urban backgrounds. The use of a pet also brought the story close to home for a lot of readers. It kind of felt like she was pulling all the stops: If nothing has hit home so far, Russell wants this story to (last-ditch effort?).

Now Talk About the Writing, Elizabeth.

As always, Russell's writing was rich in detail. Also characteristic of her, those details were not aimed to paint a picture, but to create a mood. I was creeped out, and so was the character. The cursing took me a little off-guard, since there was so much more of it in this piece, but it did fit the characters and place (doesn't mean I liked it, but I'll grant her that much). Her writing is rich with adjectives and adverbs -- "We stood on the dirty tarmac of the sidewalk, bathed in a deep-sea light. Even on a nonscarecrow day I dreaded this, the summative pressure of the good-bye moment." Definitely not minimalist; approaching maximalism while not making the narrator sound too old (probably helped by modern, coarse vocabulary). Still, his vocab use shows he's grown up because of the experience; since it is told in the past tense, we assume he's looking back and telling the story.

Also: I read something online about Russell being a concept writer -- her stories revolve around concepts more than story line or character. I completely agree with this, though the term is new to me. Maybe this is part of why she comes across as slightly didactic. I'm a bit of a concept writer, too. I've just never thought of it that way before. I hope I don't come across ... oh my gosh, my Mortal Angel story is probably just like one of these. Supernatural in a realistic world, aimed to get a concept across. I can't believe it took me this long to realize that.

Thoughts on Philosophy

I'm taking a philosophy course this semester. Today's reading was Existenzphilosophie by Jaspers (German, 1883-1969).

While reading, I was struck with the thought that maybe philosophers are limited in their scope and viewpoint. Everything is looked at from a philosophical view, an attempt to tell the whole world they are doing things wrong. They assume flaw, then search until they find that which strikes them as flawed. The whole system, so far as I can tell, has a negative turn and bias (maybe this is the fault of my professor and my past experience with philosophy?). In their quest for truth, have they ever found people to be doing something right? We must be right in some things, because not only do they work, but they make us happy (in my opinion, that's the point: to be happy).

That's not to say philosophy is a waste -- I just think it is voluntarily blind to some things. Why try to define everything in philosophical terms, why bind it down in the philosophical world? I see this only making sense if one's religion is philosophy itself.

Philosophy is meant to be a means to the end, not the end itself. That's the thesis of this post, you could say.

One thing I liked was Jasper's line, "The real import of history is the Great, the Unique, the Irreplaceable." I have always felt something to be missing from the commonly taught explanation that history is taught so we don't repeat our mistakes. Again a negative aspect of the thing. Jaspers made me realize we teach and learn history so we can learn to be great and also come to understand the present. We are characters in a story -- how are we to understand our place in it if we don't know what came before, and how are we supposed to be heroes in any sense if we don't have examples to look to? I like this reasoning much better. All three are correct, I feel, but these two new reasons are what I would prefer to be biased toward in my view of the whole.

But should I have any bias? I think it impossible to not, since I am biased by my viewpoint. My experiences and sphere of current understanding necessitate bias. My viewpoint -- the wording itself acknowledges bias.

That is something Jaspers recognizes, actually, while discussing Kierkegaard and Nietzche: "... Authentic knowing is ... nothing but interpretation. They ... understood their own thought as interpretation." He goes on to say, "... Temporal life can therefore never be correctly understood by men." It is nice to see philosophy acknowledge its limitations -- I guess the problem, for me, is that it pretends to have no limitations and assumes it is the road to real truth for any question. Okay, and if you define "philosophy" as deep thought in general, then I'd agree. But how has philosophy come to be defined, as a study? One cannot study "deep thought." That is an individual practice augmented with communication (another Jaspers concept), communication providing outside stimulus and viewpoints (in a limited fashion). I mean to ask how the field of study is defined.

In that sense, what is philosophy? Am I being taught how to think, as is alleged, or what to think, and what to think about? I feel as if philosophers are paving roads of thought I am told to walk down in pursuance of truth. Did they find it, by forging their trail and paving that road? Some, but not all. So why must I follow it, to find only old truth that I already know (or can easily read) or come to their same dead-end conclusions? That makes no sense.

Would it not be best for me to forge my own trail (I cannot completely follow/understand other trails, anyway, as both Jaspers and Nietzche pointed out), then look to philosophers for help through those areas already plowed, as I plow them anew, for myself, coming to my own understanding? My own philosophy is more important than others', as it is the only one that will affect my actions (I could explain the reasoning here, but I'll skip it). This places my thoughts above any philosopher's, and I can (and should) look to them when I am pursuing a question they addressed (see my plowing metaphor).

Would it not be best for me to forge my own trail (I cannot completely follow/understand other trails, anyway, as both Jaspers and Nietzche pointed out), then look to philosophers for help through those areas already plowed, as I plow them anew, for myself, coming to my own understanding? My own philosophy is more important than others', as it is the only one that will affect my actions (I could explain the reasoning here, but I'll skip it). This places my thoughts above any philosopher's, and I can (and should) look to them when I am pursuing a question they addressed (see my plowing metaphor).

Here's a truth: The more I care about a question, the more I will pursue its corresponding truth. That truth, once found, will mean more to me than if I had cared less. The search would have also added understanding to it -- and understanding no philosophic text can impart, because it will have its roots in my own being. It cannot be transplanted, only shown. And no one else will have that same understanding, for no one else is me.

Conclusion: Fiction is really the best thing ever. I'll have to talk about this more later, but fiction is a way for someone to find their own answers to their own questions and come to understand them, all without having to experience it firsthand. Philosophy thinks and then tries to give direct answers, but that is not the best method to convey truth, since it isn't the best way to learn.

P.S. - My philosophy professor today defined philosophy as a way of life that consists of one trying to figure out how to live the best life (by thinking and looking at past ideas and practices) and following one's theories to that end.

While reading, I was struck with the thought that maybe philosophers are limited in their scope and viewpoint. Everything is looked at from a philosophical view, an attempt to tell the whole world they are doing things wrong. They assume flaw, then search until they find that which strikes them as flawed. The whole system, so far as I can tell, has a negative turn and bias (maybe this is the fault of my professor and my past experience with philosophy?). In their quest for truth, have they ever found people to be doing something right? We must be right in some things, because not only do they work, but they make us happy (in my opinion, that's the point: to be happy).

That's not to say philosophy is a waste -- I just think it is voluntarily blind to some things. Why try to define everything in philosophical terms, why bind it down in the philosophical world? I see this only making sense if one's religion is philosophy itself.

Philosophy is meant to be a means to the end, not the end itself. That's the thesis of this post, you could say.

|

| This is the book I was reading from, if you want to read Jaspers (and others) for yourself. |

But should I have any bias? I think it impossible to not, since I am biased by my viewpoint. My experiences and sphere of current understanding necessitate bias. My viewpoint -- the wording itself acknowledges bias.

That is something Jaspers recognizes, actually, while discussing Kierkegaard and Nietzche: "... Authentic knowing is ... nothing but interpretation. They ... understood their own thought as interpretation." He goes on to say, "... Temporal life can therefore never be correctly understood by men." It is nice to see philosophy acknowledge its limitations -- I guess the problem, for me, is that it pretends to have no limitations and assumes it is the road to real truth for any question. Okay, and if you define "philosophy" as deep thought in general, then I'd agree. But how has philosophy come to be defined, as a study? One cannot study "deep thought." That is an individual practice augmented with communication (another Jaspers concept), communication providing outside stimulus and viewpoints (in a limited fashion). I mean to ask how the field of study is defined.

In that sense, what is philosophy? Am I being taught how to think, as is alleged, or what to think, and what to think about? I feel as if philosophers are paving roads of thought I am told to walk down in pursuance of truth. Did they find it, by forging their trail and paving that road? Some, but not all. So why must I follow it, to find only old truth that I already know (or can easily read) or come to their same dead-end conclusions? That makes no sense.

Would it not be best for me to forge my own trail (I cannot completely follow/understand other trails, anyway, as both Jaspers and Nietzche pointed out), then look to philosophers for help through those areas already plowed, as I plow them anew, for myself, coming to my own understanding? My own philosophy is more important than others', as it is the only one that will affect my actions (I could explain the reasoning here, but I'll skip it). This places my thoughts above any philosopher's, and I can (and should) look to them when I am pursuing a question they addressed (see my plowing metaphor).

Would it not be best for me to forge my own trail (I cannot completely follow/understand other trails, anyway, as both Jaspers and Nietzche pointed out), then look to philosophers for help through those areas already plowed, as I plow them anew, for myself, coming to my own understanding? My own philosophy is more important than others', as it is the only one that will affect my actions (I could explain the reasoning here, but I'll skip it). This places my thoughts above any philosopher's, and I can (and should) look to them when I am pursuing a question they addressed (see my plowing metaphor).Here's a truth: The more I care about a question, the more I will pursue its corresponding truth. That truth, once found, will mean more to me than if I had cared less. The search would have also added understanding to it -- and understanding no philosophic text can impart, because it will have its roots in my own being. It cannot be transplanted, only shown. And no one else will have that same understanding, for no one else is me.

Conclusion: Fiction is really the best thing ever. I'll have to talk about this more later, but fiction is a way for someone to find their own answers to their own questions and come to understand them, all without having to experience it firsthand. Philosophy thinks and then tries to give direct answers, but that is not the best method to convey truth, since it isn't the best way to learn.

P.S. - My philosophy professor today defined philosophy as a way of life that consists of one trying to figure out how to live the best life (by thinking and looking at past ideas and practices) and following one's theories to that end.

Wednesday, January 22, 2014

Scattered Thoughts

Once, I was someone people poured their problems into. I was a vessel of troubled times, worries others had. I listened and, in my youthful way, tried to respond. Then I learned to not give advice, because I learned from myself that I don't like to receive it and that I'm not wise, nor will I ever be. So I changed into someone who is a listener only. I tell people, "I'm good at listening, and I'm also good at not giving advice." A disclaimer, in case that's what they wanted. Lately, I've become a holder of silences. "My dad passed away," someone will tell me. "Oh," I say in return. "I'm sorry." Then I do one of two things: I continue to pretend the world is spinning, even though I know it has shuddered to a stop, or I don't say anything, but absorb the silence and offer a hug or similar physical comfort. It depends on the setting, I guess. I've learned I can never truly understand someone, though I have spent a great part of my short life trying to understand. Solomon once said to God, "I am but a little child: I know not how to go out or come in. ... Give therefore thy servant an understanding heart ..." (1 Kings 3:7, 9) When I read that scripture a few months ago, I recognized it as a prayer I myself have prayed (though not so eloquently). I strive to understand, though I know it is a futile struggle. I can never completely understand those around me. That is why I am a silent comforter now; I have no words to offer that will truly comfort, nothing to give that will ease their burdens. All I can do is to accept their offering--because revealing truth is an offering, a moment wherein the teller is vulnerable, reaching out for love--and stand by their side. My hope is that the telling did the healing, and my part is to provide unquestioning, unwavering support, acceptance, and love. I am always grateful they tell me, and I do not begrudge those who keep their burdens to themselves. I am an expert at not asking. I'm sure this method is not the best, but it is the best I have come to as yet.

I wonder if Lois Lowry's The Giver is really a story about an aging man who is forgetting what he has learned over the years, but he manages to hold the knowledge and wisdom out, depositing it in a new mind to carry it onward, even when he has forgotten, or has left. A story about aging, mentors, and renewal. To be on the mentored side is ... quiet, if you'll understand what I mean by using that word in place of an emotion. It describes the feeling best, I think.

To learn on one's own begets knowledge with understanding, but being told an answer begets knowledge alone, with little to no understanding. Such is the power of fiction: it allows one to experience and gain understanding while they learn. You may be reading this post and not understand a word of it, though you think you do. I may not even completely understand it until I am much wiser. I once wrote a poem I did not understand until years later, and now it echoes in my mind at times. There is value in the search for an answer. That value is lost if the journey is cut short; the lesson is left incompletely learned, and the journey must be undertaken again, at a later time. The best mentors accompany one on the journey without taking one straight to the conclusion. I can't help but think this is why God does not give us all the answers. The purpose of my life is to learn--perhaps death is meant to come once all the learning has been done. That is what I would like to think, in any case.

Note: The painting included is by Jeremy Lipking. It is one of my favorites.

|

I wonder if Lois Lowry's The Giver is really a story about an aging man who is forgetting what he has learned over the years, but he manages to hold the knowledge and wisdom out, depositing it in a new mind to carry it onward, even when he has forgotten, or has left. A story about aging, mentors, and renewal. To be on the mentored side is ... quiet, if you'll understand what I mean by using that word in place of an emotion. It describes the feeling best, I think.

To learn on one's own begets knowledge with understanding, but being told an answer begets knowledge alone, with little to no understanding. Such is the power of fiction: it allows one to experience and gain understanding while they learn. You may be reading this post and not understand a word of it, though you think you do. I may not even completely understand it until I am much wiser. I once wrote a poem I did not understand until years later, and now it echoes in my mind at times. There is value in the search for an answer. That value is lost if the journey is cut short; the lesson is left incompletely learned, and the journey must be undertaken again, at a later time. The best mentors accompany one on the journey without taking one straight to the conclusion. I can't help but think this is why God does not give us all the answers. The purpose of my life is to learn--perhaps death is meant to come once all the learning has been done. That is what I would like to think, in any case.

Note: The painting included is by Jeremy Lipking. It is one of my favorites.

Tuesday, January 21, 2014

My Totally Incomplete Reflection on Racism

I learned I’m racist while I was dating a black man.

I figured it out because the idea that my kids

may not look like me was on my mind.

A lot.

I found myself Googling whether kids born

to mixed race parents

look at all like the white one.

It turns out I learned racism in a science classroom.

No, it wasn’t from the teacher;

it was from the subject, the DNA,

studying all those recessive and dominant genes.

It wasn’t a deal-breaker,

whether or not they would look like me,

but it was something that made me uncomfortable,

a fear I only mentioned to my mother.

What are the borders of racism?

Does it count as racist to say only “people of color” should apply,

because they have too many white people

I figured it out because the idea that my kids

may not look like me was on my mind.

A lot.

I found myself Googling whether kids born

to mixed race parents

look at all like the white one.

It turns out I learned racism in a science classroom.

No, it wasn’t from the teacher;

it was from the subject, the DNA,

studying all those recessive and dominant genes.

It wasn’t a deal-breaker,

whether or not they would look like me,

but it was something that made me uncomfortable,

a fear I only mentioned to my mother.

What are the borders of racism?

Does it count as racist to say only “people of color” should apply,

because they have too many white people

and they want an interracial population?

Sounds racist to me.

But if a white person doesn't do it,

people point and say they are racist

for only having white people.

But not for only having black people,

because society says you can’t not give a black person a leg-up.

Isn’t that racist?

And you know what, I’ll own it here and now that I’m a believer in the Bible

and I do honestly believe that stuff about skin color

being a mark from God.

I just don’t think it still applies.

Ancestors from so far back they don’t even have gravestones,

their actions and sins and ideas shouldn’t be held against you.

Sounds racist to me.

But if a white person doesn't do it,

people point and say they are racist

for only having white people.

But not for only having black people,

because society says you can’t not give a black person a leg-up.

Isn’t that racist?

And you know what, I’ll own it here and now that I’m a believer in the Bible

and I do honestly believe that stuff about skin color

being a mark from God.

I just don’t think it still applies.

Ancestors from so far back they don’t even have gravestones,

their actions and sins and ideas shouldn’t be held against you.

You've never even met them.

But does that mean that God is racist?

I once saw the head prosecutor for the Rwanda trials

give a presentation to a room full of college students.

I didn’t look at him and think, “That’s one cursed dude.”

No, I looked at him and God whispered to me,

“That’s somebody special. He’s a somebody.”

The man radiated God to me.

He was black.

So even if God used to be racist, He isn’t anymore.

But God has said He never changes,

so I guess He wasn’t racist to begin with.

Maybe it’s just a big misunderstanding,

something blown out of proportion.

A misread signal, or

a signal taken way too far.

Martin Luther King had a dream

that little black boys and black girls would join hands

with little white boys and white girls.

I did that: held hands with a black man,

while I was dating a black man.

And you know what? I dumped him.

Is that racist?

No, because I didn’t make that decision based on the color

of his skin.

I did it based on the content of that man’s character.

I don’t know if society today is more racist or not

than it used to be.

The only way to be completely non-racist is to ignore race altogether.

But race is part of identity,

so it should never be ignored.

I guess I just think I should not have to ask

for the Caucasian-colored crayon.

Just hand me the box

and let me recognize the colors without ranking them,

let me use the new crayons, the broken crayons, the flat crayons,

let me pick my favorites and color a landscape

that’s just a landscape, not some assertion

that green is the best color because it’s used the most.

I used it the most because there’s a lawn with some trees.

You see, the thing about lawns and trees,

is that when they’re healthy—

they’re green.

But does that mean that God is racist?

I once saw the head prosecutor for the Rwanda trials

give a presentation to a room full of college students.

I didn’t look at him and think, “That’s one cursed dude.”

No, I looked at him and God whispered to me,

“That’s somebody special. He’s a somebody.”

The man radiated God to me.

He was black.

So even if God used to be racist, He isn’t anymore.

But God has said He never changes,

so I guess He wasn’t racist to begin with.

Maybe it’s just a big misunderstanding,

something blown out of proportion.

A misread signal, or

a signal taken way too far.

Martin Luther King had a dream

that little black boys and black girls would join hands

with little white boys and white girls.

I did that: held hands with a black man,

while I was dating a black man.

And you know what? I dumped him.

Is that racist?

No, because I didn’t make that decision based on the color

of his skin.

I did it based on the content of that man’s character.

I don’t know if society today is more racist or not

than it used to be.

The only way to be completely non-racist is to ignore race altogether.

But race is part of identity,

so it should never be ignored.

I guess I just think I should not have to ask

for the Caucasian-colored crayon.

Just hand me the box

and let me recognize the colors without ranking them,

let me use the new crayons, the broken crayons, the flat crayons,

let me pick my favorites and color a landscape

that’s just a landscape, not some assertion

that green is the best color because it’s used the most.

I used it the most because there’s a lawn with some trees.

You see, the thing about lawns and trees,

is that when they’re healthy—

they’re green.

Friday, January 17, 2014

Wherein Elizabeth Discovers She Doesn't Understand Conflict

I've realized something interesting: While my time at SUU has helped me become a much better writer, it has not done a lot to teach me the mechanics of storytelling itself. Like, I haven't even been taught about climaxes outside of a Young Adult Literature class where I was taught about the archetypes generally seen in, well, in young adult literature. I learned a lot in there, and my writing really has improved from the instruction of my wonderful professors.

My good friend T.S. I use this name for her because it is the name she writes under is knowledgeable in this area. Actually, we balance each other out quite well. T.S. has skill in looking at a story as a whole, and she is a discovery writer (she does not know the story line ahead of time). I have good focus when it comes to word choice and detail, and I am a writer who has to think first, then write. So when we look at one another's work, it is almost always a good thing. T.S. is also a lot faster at writing than I am, and therefore writes more. I can spend at least a year thinking before I start working on a story. By "thinking," I mean research and reflection. For instance, today, I spent some time looking up heart extraction online. I was doing this research not so I can get the concrete details, but so I can properly form my ideas. I don't know whether or not I will need to include heart extraction in the story I'm working on, but I am putting together a culture, and heart extraction is incidental to that culture I am creating. Hypothetically, I will tell you about it later. A lot later. So don't hold your breath.

T.S. was reading through the script I wrote for 24-Hour Theatre, and she told me something she has told me again and again: the story lacked conflict. Here's a snippet of that conversation (we were Google chatting, or hanging out on Google, or whatever it's called):

Me - And if I don't want my characters arguing?

T.S. - No, no, no, conflict isn't just arguing. Conflict is a difference of goals.

Me - Which would mean they would argue, yes?

T.S. - Say there's a boy who is in love with a girl, but the girl has no interest whatsoever. Do they argue? No, but it's conflict. The prissy cheerleader ignores or insults the nerdy boy, or she's nice to him, but doesn't agree to go on a date. Or she friendzones him. Conflict between the scientists could be the serious one is trying to keep the silly one safe or in check without him noticing, and that's why he brings the gardener in to help him, for whatever reason, because the serious one's goal is to keep the silly one safe, but the silly one's goal interferes with that.

Me - Couldn't I write that in as a character thing and tell the actors to act that way?I'm not trying to do less work, it just makes sense that way to me.

T.S. - No, because the dialogue is the story. If there is no conflict, there is not much of a story.

Not included here, because it was something I already knew, but I might as well mention that at the end of the story, the conflict needs some sort of resolution.

I thought I would pass on the wisdom, and maybe by putting it in here, I can find it later for a reminder, too. I'm still learning. Lucky for me, I have friends who know things I don't!

That's it for tonight. I'm going to the gymnastics meet with my roommates. Go T-Birds!

My good friend T.S.

T.S. was reading through the script I wrote for 24-Hour Theatre, and she told me something she has told me again and again: the story lacked conflict. Here's a snippet of that conversation (we were Google chatting, or hanging out on Google, or whatever it's called):

Me - And if I don't want my characters arguing?

T.S. - No, no, no, conflict isn't just arguing. Conflict is a difference of goals.

Me - Which would mean they would argue, yes?

T.S. - Say there's a boy who is in love with a girl, but the girl has no interest whatsoever. Do they argue? No, but it's conflict. The prissy cheerleader ignores or insults the nerdy boy, or she's nice to him, but doesn't agree to go on a date. Or she friendzones him. Conflict between the scientists could be the serious one is trying to keep the silly one safe or in check without him noticing, and that's why he brings the gardener in

Me - Couldn't I write that in as a character thing and tell the actors to act that way?I'm not trying to do less work, it just makes sense that way to me.

T.S. - No, because the dialogue is the story. If there is no conflict, there is not much of a story.

Not included here, because it was something I already knew, but I might as well mention that at the end of the story, the conflict needs some sort of resolution.

I thought I would pass on the wisdom, and maybe by putting it in here, I can find it later for a reminder, too. I'm still learning. Lucky for me, I have friends who know things I don't!

That's it for tonight. I'm going to the gymnastics meet with my roommates. Go T-Birds!

24-Hour Theatre, Last and Again

For the third time and the last time, I participated in the student-led production 24-Hour Theatre this past weekend. Looking at my past posts, I am mildly scandalized to notice I didn't write a post about it back in August. I did mention that I was not able to participate in January 2013, but that isn't as exciting.

24-Hour Theatre is just what it sounds like. At 5 p.m. on Friday, everyone gets together to meet their group, composed of a writer, director, and actors. The writer is given something to use as inspiration, and they are all dismissed. The script is due at 6 a.m. Saturday, and after that, the 10-minute play goes onstage at 7:30 p.m. (because that first meeting is kind of long, and also, because I guess it really is longer than 24 hours, strictly speaking).

The theme for all these inspirational items this semester was "travel food." I was given fruit snacks. There is little, if anything, inspirational about fruit snacks. Usually, items don't provide inspiration for me, anyway. I went online and looked up the history of fruit snacks, and it's from that that I found the concept for my play; there was a website that said fruit snacks were created when a Mr. Rupert Snacks invented them in an effort to move toward a plant-free world. I admit much skepticism to the accuracy of this, especially since the guy's last name was "snacks," but I decided it was an interesting concept that I wanted to work with anyway.

I did minor research, received some helpful feedback from my good friend T.S. (I will talk about this feedback from her in a later post), and got to sleep around 2 a.m. My finished script had three male characters two scientists and a gardener and included a chemical experiment to be performed onstage. This experiment had involved some primary research on my part; I did it twice in my kitchen sink to make sure it would be safe and large enough for audience observation. I recorded it and put it up on Facebook as a sort of advertisement for the show. I'm including the video here so you can also enjoy my kitchen experimentation.

When I came to the 6 a.m. meeting, I had with me the script and the tools and ingredients necessary to perform my experiment. I gave them to my group, hung around until I was sure they had no questions for me, then went back to bed for a morning nap.

In total, there were six of these mini-plays. I actually had two directors, though I'm not sure why, and they decided against doing my experiment. I was disappointed about that, especially since I had included enough ingredients to do the experiment twice, once in practice and once onstage. I even gave them a cookie sheet so they wouldn't make a mess. I'm under the assumption that they thought me juvenile, an idea that comes from the reaction I got from one of the directors when she found out I had brought them the stuff to actually do the experiment and had tested it in my kitchen sink. She said something like, "Oh, how cute." To be honest, I'm still a bit upset about it. I'm not used to not being taken seriously. I included the experiment because it fit in the story and because I thought it would be a cool addition to the show. I'm mostly upset that they didn't even try it. If they had tried it and decided it wasn't a good idea, that would have been okay. But they did not even do that little. Grrrr.

They also cut down my script, but I am chalking that up to time constraints. It was supposed to be 10 to 15 minutes, and it was around the 15 mark. The performance was just under 10 minutes. It still made sense, so I'm not upset by that at all.

Here's a video of the performance! I hope you like it, though you're going to have to excuse the shaking. My hands have never been steady. I'm also going to copy and paste a portion of the script here. I was going for comedy, obviously, which is not usually my strong point. I can put funny in something, but for something to be purely funny is not my strength. Practice makes perfect, though. I chose a comedy because there wasn't time for anything else, really. The play is called "A Plant-Free World."

24-Hour Theatre is just what it sounds like. At 5 p.m. on Friday, everyone gets together to meet their group, composed of a writer, director, and actors. The writer is given something to use as inspiration, and they are all dismissed. The script is due at 6 a.m. Saturday, and after that, the 10-minute play goes onstage at 7:30 p.m. (because that first meeting is kind of long, and also, because I guess it really is longer than 24 hours, strictly speaking).

The theme for all these inspirational items this semester was "travel food." I was given fruit snacks. There is little, if anything, inspirational about fruit snacks. Usually, items don't provide inspiration for me, anyway. I went online and looked up the history of fruit snacks, and it's from that that I found the concept for my play; there was a website that said fruit snacks were created when a Mr. Rupert Snacks invented them in an effort to move toward a plant-free world. I admit much skepticism to the accuracy of this, especially since the guy's last name was "snacks," but I decided it was an interesting concept that I wanted to work with anyway.

When I came to the 6 a.m. meeting, I had with me the script and the tools and ingredients necessary to perform my experiment. I gave them to my group, hung around until I was sure they had no questions for me, then went back to bed for a morning nap.

In total, there were six of these mini-plays. I actually had two directors, though I'm not sure why, and they decided against doing my experiment. I was disappointed about that, especially since I had included enough ingredients to do the experiment twice, once in practice and once onstage. I even gave them a cookie sheet so they wouldn't make a mess. I'm under the assumption that they thought me juvenile, an idea that comes from the reaction I got from one of the directors when she found out I had brought them the stuff to actually do the experiment and had tested it in my kitchen sink. She said something like, "Oh, how cute." To be honest, I'm still a bit upset about it. I'm not used to not being taken seriously. I included the experiment because it fit in the story and because I thought it would be a cool addition to the show. I'm mostly upset that they didn't even try it. If they had tried it and decided it wasn't a good idea, that would have been okay. But they did not even do that little. Grrrr.

They also cut down my script, but I am chalking that up to time constraints. It was supposed to be 10 to 15 minutes, and it was around the 15 mark. The performance was just under 10 minutes. It still made sense, so I'm not upset by that at all.

Here's a video of the performance! I hope you like it, though you're going to have to excuse the shaking. My hands have never been steady. I'm also going to copy and paste a portion of the script here. I was going for comedy, obviously, which is not usually my strong point. I can put funny in something, but for something to be purely funny is not my strength. Practice makes perfect, though. I chose a comedy because there wasn't time for anything else, really. The play is called "A Plant-Free World."

Scene: Hal

Fletcher is incredulously reading a document.

As he reads,

its contents are recited for the audience

by Dr. Morgan

and Dr. Coeden.

Dr.

Morgan:

Fact: Plants can turn people into zombies. Look up “Colombian

Devil’s Breath” for details.

Dr.

Coeden:

Fact: A tree at Southern Utah University attacked

the South Hall roof just this past October.

Morgan:

Fact: Plants are known assassins. Hemlock killed

Socrates, White Snakeroot killed Abraham Lincoln’s mother when he was only nine

years old, and there is a man-eating plant called Audrey 2 out there somewhere.

Coeden:

Fact: Every year, 68,847 people are killed by

plants. On average, animals in the United States only kill 200 per year, total.

Morgan:

Fact: Even God doesn’t like plants. He cursed Cain

for so much as offering Him some.

Coeden:

Fact: Peaceful plants take a lot of time, energy,

and money to maintain.

Morgan:

Conclusion: We must eradicate all plants on Earth

for the good of not

only the human race, but for the planet itself.

Signed, Dr. Dylan Morgan, Ph.D.

Coeden:

and Dr. Robert Coeden, Ph.D.

Fletcher puts

paper down and

makes a phone

call. Coeden answers.

Coeden:

Fletcher?

Fletcher:

So let me get this straight. Because plants attack

buildings, take up time and money, are serial killers and may cause a zombie

apocalypse, you want me to join the team and help annihilate all of the plants

in the entire world?

Morgan:

(Grabs phone) Exactly.

And the best part is that God won’t kill us for doing it, since He’s on our

side.

Coeden:

(Wrestles

phone back from Morgan) Yes, we’d like your help. You ARE a plant expert,

after all!

Fletcher:

Dr. Coeden, I’m a GARDENER at the building where you

and Dr. Morgan work! I can’t help you get rid of plants! Plants are how I make

my living!

Coeden:

(To

Morgan) He’s really excited about helping us, Dr. Morgan. Why don’t

you go … do some more research.

Morgan pulls

out his phone

and starts

looking things up.

Coeden:

Fletcher, I need you up here. Ever since Dr. Morgan

almost blew up our fume hood, I can’t concentrate without someone here to help keep

an eye on him. Come up here, and we’ll talk about it, okay? (Silence) All right, I’ll pay you. Just

get over here.

Fletcher:

How much?

Coeden:

We’ll talk about it when you are here! (Hangs up)

Fletcher:

I’m not a babysitter, and this isn’t an old folks’

home. It’s a university, for crying out loud!

Fletcher grudgingly

joins

Coeden and

Morgan. He tries to

talk to Coeden,

but Morgan interrupts.

Morgan:

All right, men. I’ve been thinking this over

carefully, and I have determined we need to go about this scientifically, using

the scientific method to figure out a safe, humane way to get rid of every

plant species on the planet without killing anyone. First, we must ask a

question.

Fletcher:

What?

Morgan:

No, that question is too broad.

Coeden:

I’ve got one: How do we kill all the

plants without killing any people?

Morgan:

I think you have gotten to the heart of

the matter.

Coeden:

The scientific method is something I pride

myself on, Dr. Morgan. I teach it to my students.

Morgan:

Our next step is to do background

research. Let’s get started.

The two

scientists begin to inspect the

background

scenery of the stage/scene

Coeden

following Morgan’s lead in this

and also

moving so as to avoid Fletcher,

who is trying

to corner him.

Morgan:

Now, enough of that. I think we have inspected the

background thoroughly. We must now construct a hypothesis.

Fletcher:

(Sarcastically)

I hypothesize that if we collect all of humanity and the animals into a

single location that contains no plants, such as this room we are standing in, and

then start a wildfire, we will be able to destroy every plant in the whole

bloomin’ world.

Morgan:

Ah, but my dear Fletcher, you have not accounted for

the nasty plant habit of springing up out of ashes like deadly green phoenixes.

I suggest we search the Internet.

Coeden:

I concur.

Morgan pulls

out his phone

to search the

Internet.

Morgan:

Google Search, “How best to kill plants.” (Searches, clears throat) First result. “Best way to kill an entire garden of

plants? Chemicals, mixture, solutions.” Let’s see what they say. “Napalm.”

Coeden:

Excellent suggestion! Our budget won’t

cover that. (Looks skittishly at

Fletcher, who gives him a

scathing look.)

Morgan:

Then I shall try another link. “How to Kill a

Plant.” No, that won’t do. There’s too much to read. Ain’t nobody got no time

for that, as the young people say. How about, “A Quick Way to Kill Plants.”

This happy old woman in overalls and a sun hat says spraying a plant with

herbicide will quickly kill it.

Morgan puts

his phone away.

Thursday, January 9, 2014

What's Elizabeth Reading? ... Russell, but also, reading notes, people.

I'm in a contemporary literature class this semester.

Speaking of classes, I have something to say. This is my last semester as an undergraduate student; I graduate in May. It's something that hit me while I was registering for my classes for this semester. I realized this is my last chance for classes at SUU (unless I came back and got a different degree, which I'm not planning on or even considering), which made me disappointed about all the classes I will not be able to take. I am taking a physics course (for fun. Science classes give great story ideas), a physics lab to go with the course, a script analysis class, a philosophy course on existentialism, an advanced poetry class, and this course on contemporary literature. The Contemporary Lit. professor has given the class a hashtag, by the way: #literaturenow

Too bad I can't use hashtags on a blog. Maybe they'll do that in the future. It sounds like a good idea.

That's a lot of classes. I say this because I'm not sure if you can tell. I am also taking an Institute class, which is kind of like a Bible study class, but for LDS (Mormon) people. So along with all that schoolwork, I'm also learning about the Old Testament twice a week. Love that.

I was considering dropping a class because I realized the work load is going to be overwhelming. Then I looked at the classes, trying to figure out which one I would want to drop, and the thing is, I love each of those classes and sincerely want to be in them. So I'm going to tough it out and hopefully not become clinically insane before the semester is out.

As I was saying, though, I'm taking this contemporary literature class, and the first book the professor has assigned is Vampires in the Lemon Grove by Karen Russell. It's a collection of short stories, so I didn't think I would post about it, but then I realized you might just be interested in the notes I'm taking. I don't generally take notes while I read — I'm more apt to write in the book itself than do anything else — but the professor has asked us to fill a notebook with reading notes this semester. So this is how I handled it. I'm still not completely sure whether I'm posting these notes for you or for my future use, but I'm posting them either way. If I like it enough, I might use the format again ... for myself and on this blog. :-)

As I was saying, though, I'm taking this contemporary literature class, and the first book the professor has assigned is Vampires in the Lemon Grove by Karen Russell. It's a collection of short stories, so I didn't think I would post about it, but then I realized you might just be interested in the notes I'm taking. I don't generally take notes while I read — I'm more apt to write in the book itself than do anything else — but the professor has asked us to fill a notebook with reading notes this semester. So this is how I handled it. I'm still not completely sure whether I'm posting these notes for you or for my future use, but I'm posting them either way. If I like it enough, I might use the format again ... for myself and on this blog. :-)

The first story is Vampires in the Lemon Grove. I chose my own format for making notes, but I kind of like the layout. First is a general response to the story, then come the answers to two separate questions.

So here goes, I guess.

Vampires in the Lemon Grove

I enjoy how Russell writes - there is enough detail to help me imagine without being burdened down with images. The vampire twist was original and left me with questions; I wasn't confused, but experienced a healthy curiosity.

What Makes This Story Work?

I think the story works because we join the narrator in confusion over the vampire figure. Both Clyde and the reader are left wondering what a vampire's purpose is, and we get no real clue from Magreb, Clyde's wife. Maybe it reflects our society's confusion over traditional roles being upset, questioned, and even abandoned.

Now Talk About the Writing, Elizabeth. (Yes, that's what I actually wrote. Also, SPOILER ALERT)

There is a lot of self-reflection in this piece, as well as an obvious use of symbolism that comes off a little heavy-handed. The movie is their relationship, Magreb is a real vampire (cave, bat-hood, etc.) while Clyde never learned what that even meant, etc. Russell uses precise details, but her ending is (disappointingly) vague, filled with overblown images and unexplained ideas, leaving the casual reader confused. *Even casual readers need to be catered to.* The decreased lucidity of the story starts after he attacks Fila (where he loses his humanity, but finds himself still trapped in that body?).

Reeling for the Empire (the second story)

This story is similar in environment to Women of the Silk, except written by a much more talented writer. Both stories involved Oriental (is that word still politically correct? Sigh) silk factories basically run by girls whose entire lives are the silk work, and both factories are owned and controlled by distant men. It is an interesting connection.

What Makes This Story Work?

What Makes This Story Work?

It is different and disturbing, and the characters seem to agree with that. They are even more painfully aware of it than the reader, though the hand-rupture thing doesn't seem to faze them like it did me. It's not remotely believable, but it is definitely intriguing - I think this results from the concept, unhindered by bad writing.

Now Talk About the Writing, Elizabeth

I think believability would have been enhanced by more description of place and the emotions, sensations, and mentality incidental to the physical change and exclusion from the outside world (the latter of which was not touched on). I needed more experience detail, I guess you could call it. Again, however, Russell includes concrete detail, and she does so well. I guess I just want it in other aspects of her story. I think the story is also missing the Japanese culture it deserves. She includes an easily identified villain, which is not usual for a contemporary work. Her villain is the Agent, who has no real name. This dehumanizes him. The kaiko-joko (as she calls them) have names, however, making them just as or more human than the human Agent. This is a traditional device, but Russell puts it to good use that was not painfully apparent.

Speaking of classes, I have something to say. This is my last semester as an undergraduate student; I graduate in May. It's something that hit me while I was registering for my classes for this semester. I realized this is my last chance for classes at SUU (unless I came back and got a different degree, which I'm not planning on or even considering), which made me disappointed about all the classes I will not be able to take. I am taking a physics course (for fun. Science classes give great story ideas), a physics lab to go with the course, a script analysis class, a philosophy course on existentialism, an advanced poetry class, and this course on contemporary literature. The Contemporary Lit. professor has given the class a hashtag, by the way: #literaturenow

Too bad I can't use hashtags on a blog. Maybe they'll do that in the future. It sounds like a good idea.

That's a lot of classes. I say this because I'm not sure if you can tell. I am also taking an Institute class, which is kind of like a Bible study class, but for LDS (Mormon) people. So along with all that schoolwork, I'm also learning about the Old Testament twice a week. Love that.

I was considering dropping a class because I realized the work load is going to be overwhelming. Then I looked at the classes, trying to figure out which one I would want to drop, and the thing is, I love each of those classes and sincerely want to be in them. So I'm going to tough it out and hopefully not become clinically insane before the semester is out.