I daresay there shall be fewer notes in this post, mainly because I took fewer notes for this season of the

Writing Excuses course.

1. With an epic, start with a small, personal plot, then make it huge.

Stories are about people, even those that are plot-driven. The interesting thing is how people react to what is going on, how they interact with their environment. That said, when you are writing an epic (read: story of enormous proportions, affecting the entire world, e.g.

Lord of the Rings)

|

In case you were wondering, this

is what people are searching for most

on Google today (updated 45 minutes ago).

Tangent much, Elizabeth? |

I am going to interrupt myself for a minute. I just typed "epic" into my URL bar to check my definition and the suggestions that came up were as follows: epic rap battles of history, epic fail, epic meal time (no idea what that one is), epic exchange (or that one), and epic sports (you mean, like, extreme sports?). This is comparable to when I tried to Google "average length of a letter" and the first few pages were about things like cover and recommendation letters, average word length in the English language (4.5 letters), the size of paper itself, and font size. I was asking about writing personal letters, the ones you put in the mail, with a stamp. What is up with this, Internet? Sigh.

Internet definition of an epic: "a long film, book, or other work portraying heroic deeds and adventures or covering an extended period of time."

Back to what I was saying two paragraphs ago, when you are writing an epic, you need to start with a personal story. Ex) Vin is an abused little girl in a thieving crew. Then gradually lead your reader into the epic so that they are grounded in character but the scope of consequences is huge. Ex) Vin becomes the person upon whom the fate of the world rests—but notice, if you're familiar with

Mistborn, that she still has tendencies and trains of thought that bring back her beginnings, her personal subplot.

2. Have your characters describe each other, not themselves.

Remember how

Catcher in the Rye starts?

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

And as far as I remember, he holds to that, never telling the reader much about himself beyond what is apparent in his narrative style and interactions with others. This is the way to do it with first person.

As for third-person narration, it is perfectly fine for Rabbit to tell Piglet that Tigger is inconsiderate, always bouncing in his garden and ruining everything. It is not fine for Tigger to turn to Piglet and say the same thing about himself. (I don't think Rabbit ever tells Piglet this, but you get my point.) It would be weird for Tigger to do that. I think the only time when a character should be talking about themselves that way is if they are supposed to be especially conceited or else they are going through therapy at the time and are talking to their therapist.

If you are having trouble describing a character without outright saying something, have another character say it about them. "And please get some coffee for the boss before you come in, she's being a nightmare," has more punch to it than "She was in a terrible mood." It also does not interrupt your story nearly as much.

Of course, actions speak louder than words, so I'd have the boss slamming doors or whatever it is she does when she's upset.

3. Switch viewpoints = switch storylines

I am waiting for the day when Microsoft Word and Blogger realize "storyline" is one word. Apparently that is not today.

|

For the record, the "Do You Want

to Build a Snowman?" song

is my favorite from the movie. |

I had never thought of it this way, but if you are using multiple viewpoints in one story, that means you have multiple main characters, each with their own dominant subplot. When you switch viewpoints, you switch from one dominant subplot to another. In Frozen, when we're looking through Elsa's eyes, the story is about expectations, accepting yourself, and the love she has for her sister. Those are the ideas that evolve while we watch her. Ana's story is about love and realizing that not everything is the way she thinks it is. These ideas take precedence when we are following her, and Elsa's ideas are put on hold until we return to her viewpoint.

In real life, everyone is learning their own lessons, and we are all learning at the same time. It should be the same way in a story. It also helps readers keep things straight, preventing your characters from mixing together in the readers' minds.

4. Before switching chapters or viewpoints, finish the mini story arc.

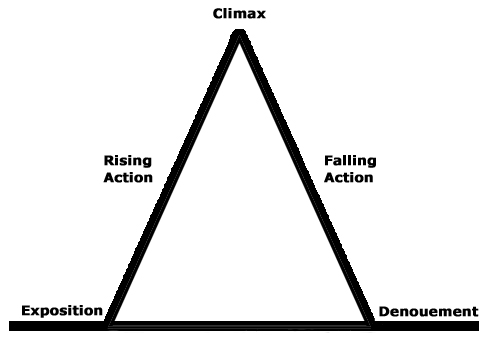

There has to be some sort of conclusion before you move on. There are miniature story arcs in each chapter or viewpoint section of a novel, and they should begin, climax, and end within that chapter or section. This does not mean you resolve everything; you just have to resolve things enough that your reader doesn't feel discombobulated by moving on. (And people think long words are fancier. "Discombobulated" does not sound at all fancy, just funky.)

|

| I have yet to see this movie, FYI. |

In The Great Gatsby:

Chapter 1: Opens by introducing narrator, ends by introducing Gatsby.

Chapter 2: We are introduced to Myrtle, Tom's mistress. It ends with Myrtle talking about Daisy so much that Tom breaks her nose.

Chapter 3: Goes through a Gatsby party (from invitation to the end), ends with Nick talking about what his normal life was like.

and so on. Notice that for each chapter, the beginning and end complement each other, just as the beginning and ending of the entire story ought to do. Your reader needs to feel some sense of closure before they can move on to another chapter or viewpoint, otherwise they will feel constantly like they are breathing in and never get the chance to breathe out. Build tension from chapter to chapter, though.

This is my lovely sketch of what your chapter/section arcs should look like. Raise the tension each time, but also give it some resolution. In this graph, height=tension. In case you were wondering.

I have to get ready for work. Make money, be responsible, that sort of thing. (Read while sitting in traffic during my commute ... )