|

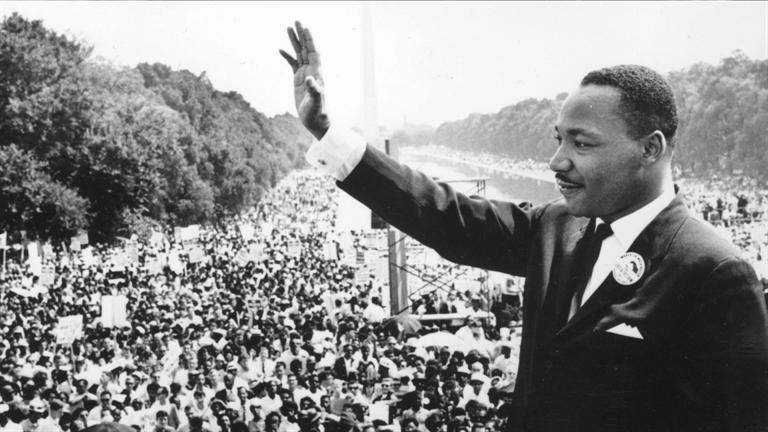

| Leo himself. Pretty intense beard. |

(Note: This post was written less than an hour after finishing Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina. My mind was still reeling a bit.)

I almost need to sit down and read it all again for the sake of digestion, but the first run-through took around nine months and I don't know that I want to spend that much more time on it at present. So instead, I did some reading online of others' analyses and am going to use this post to think aloud.

I spent the bulk of this book wondering what it was about. Leo Tolstoy has so many characters and storylines that I could tell he had a message to convey more than a story to tell. Luckily, he took his time getting there and so it felt like a story instead of a philosophy text.

I know, I just said it is lucky it was so long. In his defense, it came out serially. If you get a few bites at a time and don't see the whole feast, you wouldn't be bowled over by it. It was meant to be read slowly.

Tolstoy addresses several themes throughout the book, and many of them would have been easier to understand were I aware of the current events and debates of the time. He wrote this for a contemporary audience and got political with it. Authors these days do it too, but you don't notice because you are living in the same world as that author.

There are some universal themes, however, most notably marriage and the aristocratic lifestyle. By "theme," I mean he is speaking to a topic without any particular message in mind. This book contains a marriage where the woman is cheated on and stays, a marriage where the man is cheated on and stays, a marriage where the spouses separate without divorcing, a new marriage, a marriage with children involved, an unwedded relationship with one child who is neglected, a healthy marriage, a man with a prostitute for a mistress, and others. Tolstoy doesn't say what is best, but he does have his characters reflect on their marriage situation. That is what I mean by theme.

His message, on the other hand, the one that transcends the era and place Tolstoy lived in, is revealed in the final pages of the book. I think I would have understood better had I known the message from the start and been able to read in light of it.

That said, I give you Tolstoy's message.

"Fyodor says that Kirillov lives for his belly. That's comprehensible and rational. All of us as rational beings can't do anything else but live for our belly. And all of a sudden the same Fyodor says that one mustn't live for one's belly, but must live for truth, for God, and at a hint I understand him! And I and millions of men, men who lived ages ago and men living now—peasants, the poor in spirit and the learned, who have thought and written about it, in their obscure words saying the same thing—we are all agreed about this one thing: what we must live for and what is good. ...

Now I say that I know the meaning of my life: 'To live for God, for my soul.'"Anna Karenina is a book about why. This universal question is the reason that despite the then-contemporary references and exceedingly high page count, it is a classic that is still read today.

You could teach an entire college writing class solely on Anna Karenina, and there is so much of it I don't even know what writing lesson I would pull for you. Here is one, though: If you are trying to be philosophical in your fiction, take your time. If your philosophical idea is good enough, it will be worth the pages it takes to get it across through story.