Rules: Find a random book, steal the first sentence, and make things up from there.

It was almost December, and Jonas was beginning to be frightened. His father had promised to return before the year was out, but the snows had already begun and nothing stirred outside their small home except the last few leaves that trembled on the trees beside the blank road. The unknown was gnawing at him in the night so that he could not sleep, so Jonas put on his heavy coat and the scarf his grandma had sent and walked outside, where the snow was glowing with moonlight and he could almost hear the stars twinkle. He walked and erased the blank road, driving an uneven line across it until his feet reminded him that he had boots beneath his bed back home, but he had not discovered his father by then and so boots would have to wait until spring, when his father would give him bear hugs every day and remind him to be careful about getting lost in the mountains where he liked to escape.

The Giver, Lois Lowry

This is me when I was 10 years old. I was old and wrinkly. At least, that's what I thought, or else I thought I would skip my prime altogether and enter old age in a month or so. They are one and the same, really; ten was ancient compared to the youthful three or four, at which age you were just beginning your education and discovering how to tie your shoes. But I was beyond learning to make a bow from shoelaces and teaching my hand to shape the letter B. When I looked in the mirror, I saw the wrinkles already growing, crows feet at the edges of my eyes when I smiled just so, my teeth falling out and implying a serious need for dentures, a hair I could have sworn was gray even though Mom assured me it was a light blonde. And so I wrote my will, and bequeathed my Barbie set to my future nieces, who I was sure would come along relatively soon, because my younger brother was seven, after all, and seven isn't so much younger than ten. That done, I visited the cemetery to find a gravestone I thought would suit me, finally selecting one that had a rose and the name Pearl Quinn on it. I took a picture of it and placed it on the refrigerator along with my will so no one would forget.

Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi

George Washington Crosby began to hallucinate eight days before he died. If you were blind and could have heard him talking, you would have assumed his deathbed to be surrounded by a family of ducks and twenty-one hamsters, all in deep mourning and doing their best to amuse the poor fellow. When he did finally die, it was while smiling at the antics of a particular hamster that had attempted to ride one of the ducks as it ran, quacking, around the perimeter of the room and out into the hall. The hamster fell off somewhere near the bookcase, where it sighed and brushed itself off, then held out a thumb (which it had been miraculously born with) for a lift back to the right rear bedpost, where his brother had taken up temporary residence for lack of room beneath the bed proper.

Tinkers, Paul Harding

Friday, September 26, 2014

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

The Story of a Rewrite

|

| You know, "rewrite" was once (is?) an occupation. Reporters would dictate the facts and quotes over the phone. |

I'm rather grateful it fell off the

bandwagon, though, considering how much my writing has improved since

then. Looking back, the story had a lot of good things going for it:

Personable characters, believable villains (since it was YA, they

were definitely villains, not just the cause of conflict), and an

intact and original magic system. Probably some other things, too,

but I don't remember them right now.

I do remember the major problem of the

piece: It had no middle.

Technically, it had one. I mean, there

wasn't a vacuum where pages were supposed to be, but what I did have

was a few chapters taking my characters straight from the beginning

to the end. Nothing important happened in the middle. They discovered

they could use magic, learned how to use that magic, then went on a

trip and defeated the villain. The only thing that happened in

between was the travel, a little character development, and no big

mishaps. Nobody messed up, nobody got seriously hurt, nobody did

anything interesting.

Since high school, I have always told

myself I would rewrite that story. At first, I was waiting so I

wouldn't feel so attached to the first version (note: not “draft.”

I had edited the manuscript in high school and had it edited by

someone else, too). I didn't want to edit it; I wanted to rewrite it

entirely. At some point, I was waiting because I wanted to figure out

a middle.

But then I got all excited to write

something and figured the time had come to give that story another

go.

My first chapter was amazing (in my

humble opinion). Here are my first few paragraphs, to give you an

idea:

Will was hiding behind a fence, crouched down, straining his neck now and then to peer over the top. He was not, of course, hiding hiding. He was lying in wait, in the midst of a midday stakeout with Alex. They were both armed with PVC pipe marshmallow guns, loaded and ready to go the minute Tristan opened the front door.

The fence smelled funny for some reason Will could not figure out, so he was doing his best to quietly breathe through his mouth. He heard a noise, something like the thumping of someone quickly coming down a flight of stairs inside. Looking at Alex, he squinted his eyes, widened them, squinted again. Alex grinned and nodded, then the two of them readjusted their feet so they were ready to bust out of there.

The door opened, and Tristan came out. The two boys yelled and jumped out from behind the fence, blowing their marshmallows at her and quickly reloading. She took off down the sidewalk. Will and Alex gave chase, whooping and doing their best to reload their guns. They had brought along especially stale marshmallows today, saved for the occasion. The boys—all of the boys, every single one of their comrades in arms—had determined today was the day.

Today, they would crush the enemy.

The enemy? The girls, of course. Sneaking, prissy, lying, cheating, conniving girls.

Encouraged

by how well things were going, I dedicated myself to writing a bit

every day, pushing the story forward. That was fine and dandy until I

realized the story was boring.

The

idea, brilliant (if I do say so myself). The writing, on par (can we

just assume I am mildly humble and just being blatant about things to

make a point?). The story, suffering.

I sent

it to a writing friend with the request that she check to see if it

had a pulse. Is the story alive, or was I forcing dead story parts

together without making a successful monster? I thought it was maybe

because I had spent so much time out of the story.

But

then I caught myself in the act of destroying the story, and I

realized what the problem was. My epiphany happened when I had the thought

that things would get interesting if I let the two kids destroy a

building. Something needed to go out of control, and it had to be

big. But no! I thought

to my muse. If I do that, everything will be derailed! They

can't destroy something and still be left alone long enough to learn

how to use magic like they are supposed to!

|

| Charles Dickens: Died while writing a mystery. The man had class. This is the one mystery that will never truly be solved; it has been stopped forever in the middle. |

Do you

see what the problem was? It wasn't the exact wording from the

original that I needed to divorce myself from; it was the story

itself. I was so stuck on the idea that this story ended this

way, with events A, B, and C, that I would not allow a middle to

affect anything in my original plot.

But

every chapter needs to affect every subsequent chapter. As I learned from my Writing Excuses course, I shouldn't be writing a chapter that

the reader can skip. I was trying to create a middle for the sake of

a middle.

But

unless it affects the end, it's a dead middle. And that is what I had

on my hands.

I

could have realized this and then thrown the original story out the

window, but I just can't distance myself that much from the original

story. It's like I know

that's how it happened, and I can't lie to the reader about it and

make something else up. That's my own problem. My own solution: Start

on something new. Ditch the story.

I am

no longer qualified to write it, at least not now. Maybe in the

distant future I can resurrect the characters and concept—but only

those, because the story itself was a dud. This, folks, is why we use a (metaphorical, in my case) #2 pencil.

I am

not advocating quitting on a manuscript. However, I will say that if

you come across a problem because you are rewriting—not editing and

not re-storying—it may be time to set the story aside. Make sure your reasoning is sound, and then remember that there are

other stories out there.

And my new story? As of right now, I don't

know the ending. And that gives me the freedom to write the truth of

the story, including a middle that matters.

Friday, September 12, 2014

Books I Would Assign if I Were a 10th Grade English Teacher

I know I'm not qualified to make this list, except in that I have a degree in English (writing, not teaching). I'm doing it anyway.

I feel like many English teachers teach the books they do because they are comfortable with them. They have been taught before; they know what to teach using them because someone taught them what to teach. They do not have to re-analyze the books. I wonder how curriculum would change if this wasn't the case? That's what I was thinking when I put this list together.

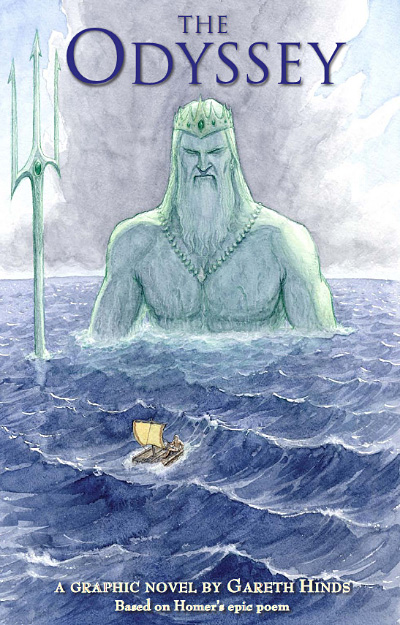

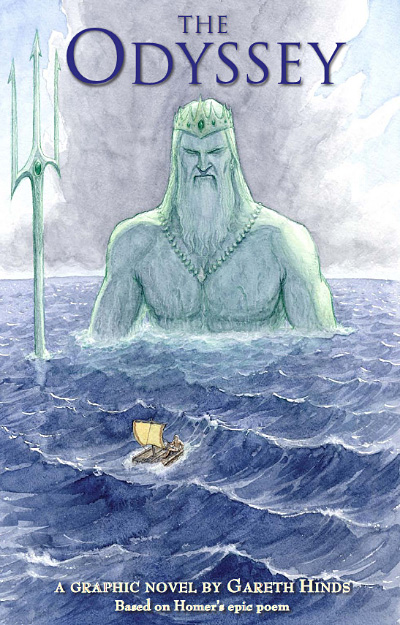

We would start off with The Odyssey by Gareth Hinds. Why this version? It's a graphic novel. The story is all there, but there are also pictures to help people clearly understand what is going on. No reason why I should make this harder than it needs to be when we're just looking at the story, in my opinion.

We would start off with The Odyssey by Gareth Hinds. Why this version? It's a graphic novel. The story is all there, but there are also pictures to help people clearly understand what is going on. No reason why I should make this harder than it needs to be when we're just looking at the story, in my opinion.

Halloween over, we would start our next unit by reading Markus Zusack's The Book Thief. Aside from loving this book, I am including it because I think WWII is something that is usually studied in the 10th grade, specifically. I remember reading Elie Wiesel, and while that gave me a great picture of the Holocaust, the books were so dark that I had a hard time reading them. I feel like The Book Thief presents the story from another angle and in a way that still lets you know how horrible it was without making you need to put the book down. Some people may say I shouldn't soften the Holocaust. I think I would bridge that with nonfiction accounts of what happened, short memoirs we would read in class and discuss.

Halloween over, we would start our next unit by reading Markus Zusack's The Book Thief. Aside from loving this book, I am including it because I think WWII is something that is usually studied in the 10th grade, specifically. I remember reading Elie Wiesel, and while that gave me a great picture of the Holocaust, the books were so dark that I had a hard time reading them. I feel like The Book Thief presents the story from another angle and in a way that still lets you know how horrible it was without making you need to put the book down. Some people may say I shouldn't soften the Holocaust. I think I would bridge that with nonfiction accounts of what happened, short memoirs we would read in class and discuss.

Next up would be our one nonfiction book, The Color of Water: A Black Man's Tribute to His White Mother by James McBride. I considered reading this right after The Book Thief, but Christmas got in the way and I decided to come at it from this angle instead. This is a book where we see someone trying to meet society's expectations and then rejecting them in favor of living the way he wants to. The mother goes through the same process, so the lesson is actually taught twice in the same book. This book would also be an avenue for discussing equality in race and religion (and gender, though that isn't directly discussed, as far as I recall).

Next up would be our one nonfiction book, The Color of Water: A Black Man's Tribute to His White Mother by James McBride. I considered reading this right after The Book Thief, but Christmas got in the way and I decided to come at it from this angle instead. This is a book where we see someone trying to meet society's expectations and then rejecting them in favor of living the way he wants to. The mother goes through the same process, so the lesson is actually taught twice in the same book. This book would also be an avenue for discussing equality in race and religion (and gender, though that isn't directly discussed, as far as I recall).

From there, we'd hit either The Hunger Games (Suzanne Collins) or Uglies (Scott Westerfield). These are both dystopian YA books, and we would use them to discuss the question "What is best?" Everyone in this world seems to believe others should live by their system of ethics. I would probably also teach some lessons in propaganda while we were at it, because people believe it and I hate seeing all the propaganda junk that comes up on my Facebook feed (there, of course, because my friends share it). As a class, we would identify which values the higher society idolizes and figure out where things went wrong. We would then apply it to now: Which values do we idolize?

From there, we'd hit either The Hunger Games (Suzanne Collins) or Uglies (Scott Westerfield). These are both dystopian YA books, and we would use them to discuss the question "What is best?" Everyone in this world seems to believe others should live by their system of ethics. I would probably also teach some lessons in propaganda while we were at it, because people believe it and I hate seeing all the propaganda junk that comes up on my Facebook feed (there, of course, because my friends share it). As a class, we would identify which values the higher society idolizes and figure out where things went wrong. We would then apply it to now: Which values do we idolize?

I would then end the year by going through a book chosen by the class. I would have the class choose the book early in the year so I have time to read it and think about it, and then we would discuss the book and the issues the book discusses. I'd end the year like that because I know they would be drowning in projects, and if they can have fun English reading, they may get their homework done. No reason why I should punish them, after all.

I would then end the year by going through a book chosen by the class. I would have the class choose the book early in the year so I have time to read it and think about it, and then we would discuss the book and the issues the book discusses. I'd end the year like that because I know they would be drowning in projects, and if they can have fun English reading, they may get their homework done. No reason why I should punish them, after all.

We would start off with The Odyssey by Gareth Hinds. Why this version? It's a graphic novel. The story is all there, but there are also pictures to help people clearly understand what is going on. No reason why I should make this harder than it needs to be when we're just looking at the story, in my opinion.

We would start off with The Odyssey by Gareth Hinds. Why this version? It's a graphic novel. The story is all there, but there are also pictures to help people clearly understand what is going on. No reason why I should make this harder than it needs to be when we're just looking at the story, in my opinion.

Why start with the story of The Odyssey? Because it perfectly illustrates the hero cycle, which is what I would be teaching, explaining that this is the basic outline for many stories. We would also probably spend some time talking about graphic novels and book layout in general. Then I would pull a fast one and introduce them to the play Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett. Waiting for Godot breaks nearly all the rules I would have just taught them; it is essentially a story with no plot. From there, we would have a discussion about what a story needs and why those parts are necessary. First unit's question, in essence: What is a story? I think it's a great place to start.

|

| Fun fact: Shakespeare's name was spelled in multiple ways during his lifetime. So no, he didn't know how to spell his own name. |

After that, we would choose another play to read, and yes, I mean "we." It being 10th grade and all, they should probably get a dose of Shakespeare. But I have a hard time deciding on a play of his I would teach, so I think I would give the class sales pitches for a few and let them choose. If one of the plays was being put on nearby, I would probably go with that show and try to go see it with them. The point of this is that everyone is expected to be somewhat familiar with Shakespeare in today's society. What I would focus on with the script would depend on which play they chose. Perhaps we would spend the unit trying to figure out why so many people care about Shakespeare. (And, through that, helping them learn why English students are taught to analyze books in the first place.)

By this time, it would be Halloween season, and one of the great things about Language Arts is we can totally celebrate holidays by reading texts that involve them. So on the week of Halloween, we would read (in class, probably) The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving and The Cask of Amontillado by Edgar Allan Poe. I chose those two because they are short stories, not full-length novels, and because they aren't Poe's The Raven. That is an amazing poem, but I trust other English classes would have introduced it. So for a breath of fresh Halloween air, I chose Sleepy Hollow (an amazing read, quite creepy) and Amontillado (even creepier). I think I would leave it at that, but if I needed to teach something with the stories, I would have the class try to figure out what it is about the stories that make them creepy. Is it just the concept, or is it also the way it is written?

Halloween over, we would start our next unit by reading Markus Zusack's The Book Thief. Aside from loving this book, I am including it because I think WWII is something that is usually studied in the 10th grade, specifically. I remember reading Elie Wiesel, and while that gave me a great picture of the Holocaust, the books were so dark that I had a hard time reading them. I feel like The Book Thief presents the story from another angle and in a way that still lets you know how horrible it was without making you need to put the book down. Some people may say I shouldn't soften the Holocaust. I think I would bridge that with nonfiction accounts of what happened, short memoirs we would read in class and discuss.

Halloween over, we would start our next unit by reading Markus Zusack's The Book Thief. Aside from loving this book, I am including it because I think WWII is something that is usually studied in the 10th grade, specifically. I remember reading Elie Wiesel, and while that gave me a great picture of the Holocaust, the books were so dark that I had a hard time reading them. I feel like The Book Thief presents the story from another angle and in a way that still lets you know how horrible it was without making you need to put the book down. Some people may say I shouldn't soften the Holocaust. I think I would bridge that with nonfiction accounts of what happened, short memoirs we would read in class and discuss.

After that, Winter Break would be fast approaching and I would have the class read Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol. It's a story they will all already know, but how many of us have read the actual story? It is a great introduction to Charles Dickens, quite accessible with plenty of wit. ... And I can't resist. I'm showing off some Charles Dickens. First two paragraphs of A Christmas Carol:

Marley was dead: to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge's name was good upon 'Change, for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a door-nail.

Mind! I don't mean to say that I know, of my own knowledge, what there is particularly dead about a door-nail. I might have been inclined, myself, to regard a coffin-nail as the deadest piece of ironmongery in the trade. But the wisdom of our ancestors is in the simile; and my unhallowed hands shall not disturb it, or the Country's done for. You will therefore permit me to repeat, emphatically, that Marley was as dead as a door-nail.

I think it is fun. The book (and it's a short one) would allow us to discuss character. Now, I may analyze books as a writer does, looking at what makes it work, but I think most people should analyze books as readers, looking at the issues being discussed. In this case, though, I would be using the book to introduce a unit where we look at people as individuals with dreams and values. This is a unit that I think would be useful when you're a teenager trying to figure out your own values, dreams, and identity.

|

| Stevenson was also the guy who wrote Treasure Island, FYI. |

Coming back from break, we would jump into The Curious Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, using the book (another short one, aren't I a kind non-teacher?) to discuss societal expectations and how people strive to meet them, sometimes destroying themselves in the process.

Next up would be our one nonfiction book, The Color of Water: A Black Man's Tribute to His White Mother by James McBride. I considered reading this right after The Book Thief, but Christmas got in the way and I decided to come at it from this angle instead. This is a book where we see someone trying to meet society's expectations and then rejecting them in favor of living the way he wants to. The mother goes through the same process, so the lesson is actually taught twice in the same book. This book would also be an avenue for discussing equality in race and religion (and gender, though that isn't directly discussed, as far as I recall).

Next up would be our one nonfiction book, The Color of Water: A Black Man's Tribute to His White Mother by James McBride. I considered reading this right after The Book Thief, but Christmas got in the way and I decided to come at it from this angle instead. This is a book where we see someone trying to meet society's expectations and then rejecting them in favor of living the way he wants to. The mother goes through the same process, so the lesson is actually taught twice in the same book. This book would also be an avenue for discussing equality in race and religion (and gender, though that isn't directly discussed, as far as I recall). From there, we'd hit either The Hunger Games (Suzanne Collins) or Uglies (Scott Westerfield). These are both dystopian YA books, and we would use them to discuss the question "What is best?" Everyone in this world seems to believe others should live by their system of ethics. I would probably also teach some lessons in propaganda while we were at it, because people believe it and I hate seeing all the propaganda junk that comes up on my Facebook feed (there, of course, because my friends share it). As a class, we would identify which values the higher society idolizes and figure out where things went wrong. We would then apply it to now: Which values do we idolize?

From there, we'd hit either The Hunger Games (Suzanne Collins) or Uglies (Scott Westerfield). These are both dystopian YA books, and we would use them to discuss the question "What is best?" Everyone in this world seems to believe others should live by their system of ethics. I would probably also teach some lessons in propaganda while we were at it, because people believe it and I hate seeing all the propaganda junk that comes up on my Facebook feed (there, of course, because my friends share it). As a class, we would identify which values the higher society idolizes and figure out where things went wrong. We would then apply it to now: Which values do we idolize? I would then end the year by going through a book chosen by the class. I would have the class choose the book early in the year so I have time to read it and think about it, and then we would discuss the book and the issues the book discusses. I'd end the year like that because I know they would be drowning in projects, and if they can have fun English reading, they may get their homework done. No reason why I should punish them, after all.

I would then end the year by going through a book chosen by the class. I would have the class choose the book early in the year so I have time to read it and think about it, and then we would discuss the book and the issues the book discusses. I'd end the year like that because I know they would be drowning in projects, and if they can have fun English reading, they may get their homework done. No reason why I should punish them, after all.

Any books I missed or that should not be in this list? Topics I focused on: story, WWII, identity, and society (and whatever the wild card books brought to the table). Along the way, the students would also learn about equality and respect for others' beliefs. Hopefully they would have fun while they were doing it.

Saturday, September 6, 2014

What's Elizabeth Reading? ...Louis L'Amour

That us what I thought until I was standing in the library, looking at a row of books written by the man and seeing that almost none of them take place in the old west. Or the modern west, for that matter. Maybe this was just the selection I was looking at, but suddenly my definition of "western" was expanded.

The book I ended up checking out was Last of the Breed, which is set in Soviet Siberia. I picked it because it was not a romance (wasn't in the mood) and the cover said it was his #1 bestseller (that totally got corrected to say "bests elder." What's up with that?).

My reason for reading L'Amour: A desire to be familiar with him because he was and is so well known in that genre. Being an author and not having read some L'Amour, I figured, was like being a children's TV entertainer and not knowing the Looney Toons.

Last of the Breed is a concept story. It asks the question, "What would happen if an American Indian was captured in Siberia and had to make his way out and back to America via the Bering Strait while evading his captors as they did everything they could do to recapture him?"

Brilliant concept, right?

This is a book to read if you love the roughing it in the outdoors. It is an adventure story. Not action, but adventure. While a few people do die, there are no fight scenes (except for when he takes down a helicopter and its three passengers, armed with only a bow and arrow, if you consider that a fight scene). There are definitely cool, adventurous moments and it is clear L'Amour knows exactly what he is talking about. I would not be surprised to hear he went backpacking in Idaho for research purposes (he keeps comparing Siberia to Idaho, and the Cold War was going on while he was writing, so I imagine he couldn't take a jaunt in the Soviet Union proper).

This is not a book to read if you want romance, fights, or a fast-moving story. He keeps circling over the same ideas, meaning this is an exposition-heavy book that is repetitive. To defend L'Amour, though, he was dealing with one man by himself much of the time, and he had to fill in all the silence somehow and keep us emotionally connected. It got a bit old for me by the end, but I would not be against rereading it.

There are multiple subplots, which he uses to keep the audience's attention, to increase tension, and to raise the stakes. Not all of these subplots are, for me, satisfactorily resolved, leaving the book open-ended. One would expect a sequel, but there isn't one.

As a random side note, this book is also extremely clean and family-friendly, minus the fact that people die and we see one couple talking the morning after they were obviously sleeping together.

My final take was that it was a brilliant concept and the right readers will love the book.

Monday, September 1, 2014

A Note About Editors

A while back, I mentioned an editor's bedside manner. I think that would be a good topic to discuss today. Why not, right?

Even though I am a writer by nature, I am an editor by trade. You might think that means my writing is perfect the first time round, but that's not true. Sure, my English is probably fine, but it's hard to see what is wrong with something you wrote. It's your baby; it's perfect! Every story, poem, article, whatever it is you have written, needs another set of eyes on it to make it better. Hopefully that extra set of eyes can see what you can't and can guide you in improving it. (Please have it edited before you submit it to a publisher! You want every advantage you can have.)

Not all editors were created equal. If you can, try to get a sample of the editor's work before you pay them anything. It's my personal practice to send half the manuscript back to the author before I ask for what they owe me, and when I get the payment, I give them the second half. That way, they know they are paying for a quality scrubbing and I can be sure I am getting paid.

Getting a manuscript back from an editor can be one of the most discouraging moments ever. You'll suddenly see just how terrible a writer you are and wonder whether the project is even worth it. Okay, you might wonder those things. I'm not you, so I don't really know. I just know that sometimes that moment makes me want to cry.

A good editor will rip your piece apart. That's the truth of it. But they should also mix compliments and jokes in with their critique. This serves to give you some confidence and also makes you feel like the project really isn't a lost cause. Plus, anything that makes you smile in that moment is greatly appreciated.

If the compliments and jokes outnumber the actual edits, you need a better editor, because they aren't doing their job correctly. You are not paying them to make you feel warm and fuzzy inside.

Some sample comments, both edits and not, that I have made before, to give you an idea of what I mean:

1. Corrections/edits (all are suggestions; note that everything an editor says is always a suggestion)

2. Reactions to the story (so the author can gauge how a reader is responding and adjust if desired)

3. FYIs (meaning, I tell the writer what they just did in case they didn't realize it and don't want to be doing that)

4. Questions (meant to urge the author to clarify or add things)

5. Compliments

6. Jokes (sometimes because a correction needs to be made that was obvious and funny, sometimes a reaction to what the characters are doing)

I do not always give suggestions for how to fix something. Depending on the writer, that can be appreciated or not. When I don't give a suggestion, it's usually because I believe this is the author's work and my solution would make it sound too much like me instead of them.

This post would be incomplete without me saying that an editor should always treat the work as yours. The writer has the final say, because it is their work and their name is the prominent one on it should it get published. An editor should work with a writer just like a coach works with an athlete. No editor should belittle you or your piece and still get paid the full amount. This is why I suggest getting a sample first, because that should show you what sort of editor the person is. The writer is the athlete, the editor is the coach, and they work together to serve the reader. The reader is the most important part of this equation. Never forget that.

This post would be incomplete without me saying that an editor should always treat the work as yours. The writer has the final say, because it is their work and their name is the prominent one on it should it get published. An editor should work with a writer just like a coach works with an athlete. No editor should belittle you or your piece and still get paid the full amount. This is why I suggest getting a sample first, because that should show you what sort of editor the person is. The writer is the athlete, the editor is the coach, and they work together to serve the reader. The reader is the most important part of this equation. Never forget that.

I'll end this post with a plug for myself as an editor. If you want me to edit your piece, leave a comment and I'll get back to you.

May the Force be with you, and happy September!

Even though I am a writer by nature, I am an editor by trade. You might think that means my writing is perfect the first time round, but that's not true. Sure, my English is probably fine, but it's hard to see what is wrong with something you wrote. It's your baby; it's perfect! Every story, poem, article, whatever it is you have written, needs another set of eyes on it to make it better. Hopefully that extra set of eyes can see what you can't and can guide you in improving it. (Please have it edited before you submit it to a publisher! You want every advantage you can have.)

Not all editors were created equal. If you can, try to get a sample of the editor's work before you pay them anything. It's my personal practice to send half the manuscript back to the author before I ask for what they owe me, and when I get the payment, I give them the second half. That way, they know they are paying for a quality scrubbing and I can be sure I am getting paid.

|

| This is one of my favorite memes ever. |

Getting a manuscript back from an editor can be one of the most discouraging moments ever. You'll suddenly see just how terrible a writer you are and wonder whether the project is even worth it. Okay, you might wonder those things. I'm not you, so I don't really know. I just know that sometimes that moment makes me want to cry.

A good editor will rip your piece apart. That's the truth of it. But they should also mix compliments and jokes in with their critique. This serves to give you some confidence and also makes you feel like the project really isn't a lost cause. Plus, anything that makes you smile in that moment is greatly appreciated.

If the compliments and jokes outnumber the actual edits, you need a better editor, because they aren't doing their job correctly. You are not paying them to make you feel warm and fuzzy inside.

Some sample comments, both edits and not, that I have made before, to give you an idea of what I mean:

I’m going to be blunt and say this sounds stupid. Try to find a different lead-in, maybe consider using an em dash.

Well, that’s a conceited thought.

What is the newbie doing, and was he at last week’s meeting?

Stereotypical

You’ve got romantic undertones going on. FYI.

Well done in showing, not telling, that her existence has been wiped out. It leaves two questions: Why is the stone for her grave still there, and why do the ghosts remember her?

This drops your audience's age from about 6 to about 3

You are making this kid symbolic for every kid; he is not unique in any way. Make him a person with an actual character, even if he only appears here. Characters who are stereotypical are lazy characters.

Oh, please. He knows she’s talking to him. This is just him being rude.When I edit, I tend to make the following types of comments:

1. Corrections/edits (all are suggestions; note that everything an editor says is always a suggestion)

2. Reactions to the story (so the author can gauge how a reader is responding and adjust if desired)

3. FYIs (meaning, I tell the writer what they just did in case they didn't realize it and don't want to be doing that)

4. Questions (meant to urge the author to clarify or add things)

5. Compliments

6. Jokes (sometimes because a correction needs to be made that was obvious and funny, sometimes a reaction to what the characters are doing)

I do not always give suggestions for how to fix something. Depending on the writer, that can be appreciated or not. When I don't give a suggestion, it's usually because I believe this is the author's work and my solution would make it sound too much like me instead of them.

This post would be incomplete without me saying that an editor should always treat the work as yours. The writer has the final say, because it is their work and their name is the prominent one on it should it get published. An editor should work with a writer just like a coach works with an athlete. No editor should belittle you or your piece and still get paid the full amount. This is why I suggest getting a sample first, because that should show you what sort of editor the person is. The writer is the athlete, the editor is the coach, and they work together to serve the reader. The reader is the most important part of this equation. Never forget that.

This post would be incomplete without me saying that an editor should always treat the work as yours. The writer has the final say, because it is their work and their name is the prominent one on it should it get published. An editor should work with a writer just like a coach works with an athlete. No editor should belittle you or your piece and still get paid the full amount. This is why I suggest getting a sample first, because that should show you what sort of editor the person is. The writer is the athlete, the editor is the coach, and they work together to serve the reader. The reader is the most important part of this equation. Never forget that.I'll end this post with a plug for myself as an editor. If you want me to edit your piece, leave a comment and I'll get back to you.

May the Force be with you, and happy September!